Abstract

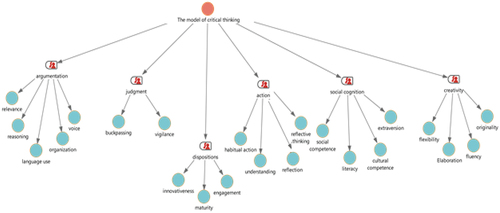

Characterizing a critically-thinker second language learner as well as the way such characteristics can be developed and implemented in instructed second language have received momentum in applied linguistics. As a novel practice, this mixed-methods study was designed to feature a critically-thinker reader in developing both her critical thinking and reading abilities in the light of two novel instructional mechanisms (i.e., Asynchronous Web-based Collaborative (AWC) vs. Question-Answer-Relationship (QAR) instructional approaches). To this end, a sample of 89 Iranian EFL learners (Pilot group) were interviewed based on which first the features of a critically-thinker reader were extracted, analyzed and modeled via MaxQDA. Then, three groups of 154 language learners (i.e., Control, QAR & AWC) were exposed to its specific type of instruction. In addition to the extraction of “argumentation”, “judgment”, “dispositions”, “action”, “social cognition”, and “creativity” each with its sub-categories as the sub-traits of critically-thinker’s conceptual model, ANOVAs were run to analyze the quantitative data. It was observed that AWC group outperformed others both in critical reading and critical thinking features. So, it is theoretically and pedagogically implied that the developments of both cognitive traits (i.e. critical thinking) and the resultant language skills (i.e. reading skill) are subject to appropriate instructional approach/s.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Reading in general and critical reading (CR) has always been an activity that requires understanding, analysis, evaluation, and interpretation of the content. Through CR it is necessary to analyze a text before combining it with one’s beliefs or making decisions. There are several views and theories of teaching CR, each focusing on some skills. But what kinds of skills and competences does a critical task require? Are analysis, interpretation, and referencing all we need during a critical thinking activity? A review of previous studies in the field of critical thinking shows the existence of two mainstreams: First, a group of studies that focus on critical thinking as an individual-personal phenomenon, and second, the group of recent studies which consider CR to be composed of individual, social and cultural factors. However, what remains a question is how to measure CR, which shaped the rationale behind this study which ends up with solutions and instruments for this question.

1. Introduction

Following the Socratic method, Gabennesch (Citation2006) introduced critical thinking (CT) as a kind of sentimental and rational thinking that helps us to achieve a worldview and knowledge of values and ultimately to get closer to the truth. Because of this, CT has always been of interest to many researchers and theorists, and many of them, including Moon (Citation2008), and Paul and Elder (Citation2006) have emphasized the need to grow and develop it as an essential skill for teachers and students. CT is supposed to contribute a lot to successful and effective development of language skills involving reading skills.

Reading is viewed as the most crucial academic skill for foreign language learners and defined by Berardo (Citation2006) as a dynamic and complex phenomenon and a source of gaining language input, reading is a receptive skill which requires an interaction among the author of the text, his/her message, and the reader to comprehend it. Reading and thinking are closely interwoven. Characterizing critically thinker language learners is a crucial and intact issue in order to exercise appropriate developmental mechanisms and approaches. Moreover, various approaches have been experimented as to teaching reading but when reading skill is integrated into critical thinking, an integrative development of both traits may require a novel approach. For example, web-based collaborative approach or question-answer based approach has rarely been both comparatively on one hand, and with respect to the integration of the mentioned variables experimented, on the other hand.

According to Brown (Citation2000), reading is an important language skill that contributes to learners’ academic success by enhancing their understanding of the content of the texts. In this regard, Chou (Citation2011) stated that to acquire and improve such ability, mastering aspects of recognizing words and their role and relationships between words, understanding the ideas and goals of the author/authors, and achieving decisions is essential. Cox et al. (Citation2003) claimed that learners will perform their tasks better if they have adequate knowledge of reading comprehension, critical thinking, and meta-cognitive skills. According to Hall and Piazza (Citation2008), critical reading is still one of the skills which helps learners gain success in academic courses whilst it is still vague to many teachers, and they usually fail to develop such skill in their students. They represented that students tend to accept more of written content than those spoken implicit messages and that if students lack the skill to analyze and challenge such content, then they will face many problems in understanding and questioning their living environment and society.

Due to the importance of critical thinking in education, it has been approached from different perspectives (Ilyas, Citation2018; Krathwohl, Citation2002; Reed, Citation1998). Halvorsen (Citation2005) also acknowledged that it is impossible to provide a simple concept for it because it takes on different meanings and dimensions for people in different contexts and cultures. However, it can be said that most of the definitions provided have comparable values and various methods have been introduced to develop this skill, including journal writing (Sinaga & Feranie, Citation2017; Stanton & Stanton, Citation2017) and critical reading (Femilia, Citation2018).

Many researchers (e.g., Lewis, Citation2000; Wilson, Citation2016) considered critical reading as an activity consisting of analyzing, interpreting, evaluating, and understanding content, and believe that in critical reading, analysis and evaluation of texts are necessary before combining their beliefs or ideas. Lewis (Citation2000) introduced critical reading as an analytical activity that causes the need to reread a text. He believed that this rereading leads to recognizing the elements of a text and the patterns between them, extracting information and assumptions and understanding the use of language in that text. There are several theories about critical reading instruction, including the theory presented on the Salisbury University (Citation2013) based on which it is necessary to introduce the following steps: previewing, contextualizing, questioning, reflecting, outlining, and summarizing, evaluating an argument, and comparing and contrasting.

Ontology and epistemology of previous studies show the existence of two mainstreams in studies related to the notion of critical thinking; First, there is a group of studies (generally old studies) that focus on critical thinking as an individual-personal phenomenon and believe that the development of critical thinking is restricted to the development of some personal skills (e.g., Bloom, Citation1956; Facione, Citation1990; Ennis, Citation1991a; Ennis, Citation1996; Epstein & Kernberger, Citation2006). In contrast, more recent studies (e.g., Danvers, Citation2016; Davies, Citation2015; Davies & Barnett, Citation2015; Elder & Cosgrove, Citation2019; Meneses, Citation2020; Mohammadi et al., Citation2022; Ramírez-Verdugo & Márquez, Citation2021; Zembylas, Citation2022) acknowledge that critical thinking encompasses a wider range of skills and competencies which, in addition to the individual factors, emphasizes the environment, community factors, cultural phenomena, learning contexts, etc. (i.e., social-cultural dimensions).

It can be inferred from Facione’s (Citation1990) standpoint that critical thinking is composed of skills such as argumentation, reflective thinking, and dispositions. In the traditional view, this concept is defined in the form of a continuous examination of a type of belief, or knowledge (Dewey, Citation1933; Glaser, Citation1941) or as the process of acquiring some skills to develop critical thinking to analysis an output, belief or idea by applying the acquired skills (Ennis, Citation1991). Meanwhile, these pioneers did not explain the influence of individual, social and environmental factors or the effects of pedagogy, educational policies, and approaches on the process of developing, valuing, and applying critical thinking in different societies. According to Paulsen (Citation2015), the traditional definitions have failed to focus on other aspects and have limited themselves to only a few individual skills, but it is necessary to know other aspects of critical thinking and determine whether those aspects can be taught to learners in different stages and disciplines. As far as academic success is concerned, reading, writing, and critical thinking are amongst the key skills that students need to be successful in their academic education, either in their first language or in second or foreign language.

In the new attitude, Davies (Citation2015) claimed that critical thinking embraces critical pedagogy, feministic approach to education, and critical citizenship of today’s world or other education-based topics that utilize the concept of criticality. Similarly, it usually refers to the significance and importance of providing learners with the opportunity to develop and improve their general skills such as reasoning. Davies (Citation2015) has suggested a model in which the basic focus is on critical thinking movement, criticality movement, and critical pedagogy movement. These movements have separate layers (i.e. elements) and each of them plays a significant role in the comprehensive model of critical thinking. The model represents that to study critical thinking in a person, it is necessary to consider both individual and socio-cultural aspects. According to Etherington (Citation2021), Birjandi et al. (Citation2019), Dekker (Citation2020), and Imperio et al. (Citation2020), CT in today’s world includes a diverse range of concepts and themes in such a way that in addition to thinking skills, intellectual tendencies are also considered; and parallel to the internal tendencies of people towards such thinking, it also emphasizes on the external obstacles and dilemmas of cultivating and applying critical thinking. They also acknowledged that the relationship between different types of thinking, such as strategic thinking, logical thinking, creative thinking, abstract thinking, associative thinking, and etc., are included in the framework of CT.

1.1. Movements of critical thinking

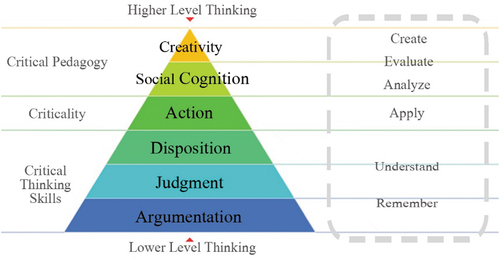

In accordance with the theoretical models presented in previous studies (Chen, Citation2019; Danvers, Citation2016; Davies, Citation2015; Davies & Barnett, Citation2015; Meneses, Citation2020; Zembylas, Citation2022), the proposed model for critical thinking in this study relies on three main movements namely individual critical thinking movement, critical pedagogy movement and criticality movement).

1.1.1. First movement (cognitive skills, judgment, and disposition)

First movement refers to Dewey’s definition of critical thinking as a dynamic, constant, and cautious thought of a conviction or assumed type of information, considering the grounds that help it, and the further results to which it tends (Wang, Citation2017) and Ennis’ definition as a sensible contemplative thinking that is centered around choosing what to accept or do (Ennis, Citation1991). According to Wang (Citation2017), this movement emphasizes more on the philosophical view of critical thinking based on which much attention is paid to the requirements of logical thinking. However, a more complete and transcendent set of elements of this movement is presented by Davies (Citation2015) as follows:

Cognitive layer (Argumentation): Epstein and Kernberger (Citation2006) defined argument as any endeavor to persuade somebody (even yourself) that a specific claim is valid.

judgment layer: According to Loving (Citation1993) and Mace (Citation2005), judgment is the ability to make critical distinctions and to arrive at sensible decisions.

Disposition layer: According to Tishman and Andrade (Citation1996), thinking dispositions are propensities toward specific patterns of intellectual behavior. Ennis (Citation1996) characterized a disposition as an inclination to accomplish something given certain conditions.

1.1.2. Second movement (cognitive skills, judgment, disposition, action)

According to Davies and Barnett (Citation2015), the second movement is related to a person’s cognitive characteristics including cognitive factors or skills such as argumentational thinking skills, reasoning ability and argumentative traits in action.

Criticality layer: In Davies (Citation2015) view, the term criticality was coined to offer a broader perspective than critical thinking, which includes not only argumentation, judgment, and reflection, but also the broader identities of individuals and their participation in the world.

1.1.3. Third movement (cognitive skills, judgment, disposition, action, social cognition and creativity)

The last movement is defined as an attitude towards teaching language which connects classroom context to social context (Akbari, Citation2008; Davies & Barnett, Citation2015; Pennycook, Citation1990). According to Wilson (Citation2016), this approach to critical thinking refers to the student’s ability to act responsibly and ethically.

The social cognition layer: In the view of Davies (Citation2015), this component of critical thinking is limited to a person’s social class and occupation; while Padilla and Perez (Citation2003) stated that this layer focuses on social cognition, which is in fact a metatheoretical approach used to study the social behavior of individuals. In this approach, the focus is on those mental processes that shape and guide social interaction. This study also emphasizes the more comprehensive concept—i.e. social cognition—and its impact on behavior, perception and performance of individuals.

Creativity, the last layer: According to Burton (Citation2010) creativity is related to the level of achievement of second language in individuals. Simonton (Citation2006) expounded it as a multi-dimensional (verbal-nonverbal) attribute differentially distributed among people with fluency, flexibility, originality, acquisitiveness, and persistency.

Reading is viewed as the most crucial academic skill for language learners which can facilitate their social success and personal development, and reading deficiencies negatively affect aspects such as learners’ educational progress, self-esteem (confidence), attitudes towards reading and learning, employment, and socio-economic conditions (Gamboa-González, Citation2017). Therefore, in order to read, comprehend and respond to a written content, the reader is expected to have some certain skills and abilities among which are reading to grasp the message of each line and paragraph, reading to find the existing relationship between the paragraphs, understanding the basic message of the author, and finding the most appropriate answer to the idea of the writer (Berardo, Citation2006). According to Berardo (Citation2006), except for the first stage, the other stages require readers to apply a higher order of thinking namely critical reading.

1.2. Approaches of reading

Focusing on approaches to teaching reading, one can refer to instructional approaches, interactive approaches, strategic approaches, and else each with their advantages and disadvantages. According to Johnson and Johnson (Citation2008), instructional approaches let instructors determine teaching methods, strategies, skills, practices, etc. for specific instructional objectives such as collaboration or questioning.

1.2.1. Asynchronous web-based collaboration (AWC)

Collaborative learning is defined as a variety of social interaction of a group of students and instructors in the process of sharing and acquiring knowledge and gaining experiences (Su et al., Citation2010). According to Harden and Crosby (Citation2000), the concept of collaborative learning approach has gained significant attention in today’s educational system since the preferred manner of classroom management has shifted from teacher-centered to learner-centered. Wheeler et al. (Citation2008) claimed that this shift, even though it was initially established in the social constructivist hypothesis of learning, is inalienable in the modern learning advancements. According to Holbeck and Hartman (Citation2018) the emergence of new e-learning technologies over the educational community caused more requirements for the advancement of new devices and facilities which can encourage both learners and instructors.

Alhujaylan (Citation2021) and Habbash (Citation2021) showed that this approach gives students more time to analyze and reflect, as well as use different resources; increases their reasoning and critical thinking skills by writing ideas; and causes the group of students who do not tend to express their opinions in class discussions, to interact with others more easily. According to Yang et al. (Citation2011), social annotation techniques help students to pay more attention to textual information through annotations; to look at the structure and organization of the text; to index the key points and important parts of the text; and finally, to discuss the text. According to Haavind (Citation2006) and Land et al. (Citation2007), the use of online discussion results in knowledge construction in students and, as a scaffold, it leads to the recognition and application of multiple perspectives, negotiation of meaning, and understanding of the knowledge gap in them. In the field of technology-enhanced learning environment, Crosby (Citation1996) and Lou et al. (Citation2001) showed that being active in small learning groups leads to active learning, increased self-motivation and idea development, deep learning promotion, and transferable skills development.

1.2.2. Question-answer relationship (QAR)

On the other hand, Question-Answer-Relationship (QAR) Instructional Approach is a comprehension strategy that empowers students to find the information that they need in order to effectively respond to questions. In this view, one can refer to the four sources of information within QAR: Right There (i.e. search for the answers in the text), Think and Search (i.e. think about how the provided ideas and information are related), Author and Me (i.e. use the provided ideas and yours to find answers), and On My Own (i.e. use your background knowledge to answer), by Raphael et al. (Citation2006). According to Raphael et al. (Citation2009), strategies such as QAR, consisting of explicit instruction in the use of questions to support reading, may be effective with diverse learners who are often thought to be less capable of higher-level thinking and, therefore, rarely talk about texts. They claimed that QAR provides students with common language and comprehension strategies to foster critical thinking abilities. Furtado and Pastell (Citation2012) showed that this strategy improves students’ reading comprehension scores. Nugroho (Citation2012) also showed in his study that in Indonesia, students who have been trained using this technique perform better in the post-comprehension test. According to Geothals et al. (Citation2004) and Yang (Citation2017), asking questions in the classroom plays a key role in the process of understanding the text, teaching, and learning, and helps learners participate in class activities faster. The study of comprehension and critical thinking skills by Untailawan (Citation2020) shows that QAR promotes both variables. Peng et al. (Citation2007) also showed that this strategy significantly increased students’ self-confidence and effort to understand the text.

Explaining the educational philosophy of this study, it should be mentioned that research in the field of education is about exploring, recognizing, and understanding social phenomena that have an educational nature and affect educational processes. According to Schoeman and Mabunda (Citation2011), this form of research has education-related research questions and can be conducted in a satisfactory manner and provides useful and practical results. Research questions in education also generally originate from perceptions and interpretations of social realities and human needs, and therefore different paradigms have been developed to determine the criteria on which the method for conducting research can be selected. According to Callaghan (Citation2016), by recognizing and comprehending a certain paradigm, one can observe the world in a special way, and Kivunja and Kuyini (Citation2017) and Pabel et al. (Citation2021) considered the paradigm equivalent to worldview since it introduces how a researcher understands and perceives the world around the subject, the research process, the beliefs that have influenced the research design, how it is implemented, and how the results are presented. The paradigm admitted for this research (hybrid methods research) was the dialectical perspective and both the pragmatism and transformative-emancipatory paradigms were applied in conducting the research. Using pragmatism model, it was tried to combine deductive and inductive approaches by combining quantitative and qualitative methods of research and using different methods of data assessment and analysis. Mertens (Citation2010) stated that one of the most substantial features of the transformative paradigm is paying attention to the challenges of minority groups such as EFL learners. In this regard, Teddlie and Tashakkori (Citation2009) emphasized that transformative-emancipatory scientists can utilize any research strategy that provides results which advance more prominent civil rights.

At the end of this section, it is worth mentioning that the comparison of the two introduced mainstreams represents that there is still a deep gap between the old and modern attitudes towards critical thinking and both attitudes have their pros and cons. Therefore, the current study was designed with the aim of measuring the needs of today’s educational communities to the notion of critical thinking, and to respond to one of the most effective and up-to-date scientific-educational needs. Given the discussions made, the necessity of determining the priority of these two mainstreams, as well as the importance of identifying the elements which make up critical thinking in today’s education, on the one hand, and developing and assessing the constructs of critical thinkers (based on the identified elements) on the other hand, have become crucial issues to important be investigated in particular in the light of two rarely empirically and comparatively investigated instructional approaches (i.e. QAR and AWC).

2. Methodology

In this comprehensive study, an attempt was made to first extract the characteristics of a critical thinking EFL reader, then to propose a suitable tool to measure these characteristics, and finally to measure the identified criteria in different learning conditions. So, this study followed a triple purpose realized in the following research questions:

RQ1. What are the features of a critically-thinker EFL reader?

RQ2. To what extent does asynchronous web-based collaborative approach compared to QAR instructional approach lead to critically-thinker EFL readers?

RQ3. To what extent does asynchronous web-based collaborative approach compared to QAR instructional approach lead to reading skills development?

2.1. Participants

For the purpose of the study, 243 Iranian undergraduate intermediate EFL learners, aged from 18 to 35, were selected (intact classes with the average PET score above 147). The participants were classified into pilot group (No = 89), Control group (No = 51), QAR group (No = 53) and AWC group (No = 50). The issue of determining the sample size and its power has been considered in various studies and according to Malterud et al. (Citation2016) it is necessary to do this in both qualitative and quantitative studies. In qualitative studies, the concept of saturation is generally relied upon to determine sample size. This means that data collection in qualitative phase continues until the reduction of pure statements and raise in the number similar responses. Malterud et al. (Citation2016) introduced the concept of information power to determine the sample size and stated that the more information power participants have, the less number of participants; Thus, the sample size depends on the purpose of the study, the specificity of the sample, the established theory, the information power and quality of the interviews, and the researcher’s analysis strategy. This article represents part of the results of a comprehensive study on characterizing a three-dimensional critical thinker. In the qualitative phase of this research, participant selection and interviewing continued until the saturation point was reached. In the next phases, in order to determine the size of the pilot group (to evaluate the conceptual model which is presented in the other article) and the size of the experimental groups, the Morgan Sample Size table was used.

2.2. Instrumentation

In this study, researchers tried to fill in one of the gaps in the field of critical thinking and reading comprehension by using the results of previous research. In the data collection process and in order to rely on the results of previous studies, various questionnaires were used to raise awareness in learners and to provoke their prior knowledge and with the aim of extracting different types of information and the most comprehensive characteristics of a reader with a critical mind. The use of various tools was done with the aim of triangulating the data following the process of ground theory.

Abedi-Schumacher Creativity Test (ACT) for creativity: ACT (designed by O’Neil et al. (Citation1994) and revised by Abedi (Citation2002)) was used to assess fluency, flexibility, originality, and elaboration through 56 MCI questions. According to Auzmendi et al. (Citation1996) the estimated reliability was .61.

Argument Schema Theory (AST) for argumentation: AST model of Reznitskaya and Anderson (Citation2002) and Kaewpet’s (Citation2018) rubrics were used based on which the pilot group was asked to write a 250-word reflective essay in response to the reading text.

Critical Reading Test: The researcher used SAT Critical Reading test by Weiner Green and Weiner (Citation2012) to assess students’ critical reading in two phases of pretest and posttest. The selected tests (sets number one and three) have sixty-seven questions to be answered in 70 minutes. Cronbach’s alpha calculation represented a value of .708.

Critical Thinking Inventory: The CTI inventory (Mohammadi et al., Citation2022) was used to measure the criteria of argumentation, judgment, disposition, criticality, social cognition, and creativity through 59 items of 5-point Likert type inventory. The CR and AVE were reported in the work as 0.97 and 0.687.

Hylighter program: This program (a Web 2.0 social software) was used as a collaborative platform in AWC group in order to read a text, annotations, and collaborate with each other in finding the answers.

Interview Protocol: Additionally, a six-item semi-structured interview was designed to determine the characteristics of a critically-thinker EFL reader.

Reflective Thinking Questionnaire for Criticality: Kember et al. (Citation2000) addressed factors of habitual action, understanding, reflection, and critical reflection using the 16 items Five-Likert survey. The reliability of the instrument was reported as Cronbach’s alpha of .77 in total, .621 for habitual action, .757 for understanding, .836 for reflection, and .675 for critical reflection.

Melbourne Decision Making Questionnaire for judgment: Designed by Mann et al. (Citation1997), it focuses on aspects of Vigilance, Hypervigilance, Procrastination, and Buck Passing through 22 items. They reported Cronbach Alpha coefficient of .80, .74, .81, and .87 respectively.

Preliminary English Test (PET): The test was administered to assess participants’ general knowledge of English language. The items are distributed as follows: Reading and writing (eight parts, 42 questions); listening (four parts and twenty-five questions); speaking (four parts of face-to-face interviews).

Critical Thinking Disposition Assessment for Disposition: Ricketts (Citation2003) assessed factors of innovativeness, maturity and engagement through 33 Five-Likert scale questionnaire. Its reliability was also reported as: Cronbach’s alpha of innovativeness, maturity, and engagement were 0.75, 0.57 and 0.86.

Social Statue Questionnaires: The first one was designed by Pishghadam et al. (Citation2011), named Social and Cultural Capital Questionnaire (SCCQ), was used to assess factors of social competence, social solidarity, literacy, cultural competence and extraversion through 42 items on a five-point Likert scale with reliability estimate of .88. The other one was Critical Pedagogy Attitude Questionnaire (by Pishvaei & Kasaian, Citation2013) used to assess learners’ tenets of monolingualism, monoculturalism, native-speakerism, native teacher, native-like pronunciation, and authenticity of native-designed materials through 24 items on a 5- point Likert scale with total Cronbach’s alpha reliability of .93.

2.3. Design

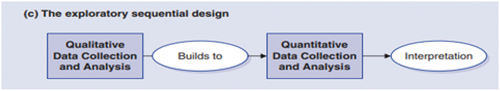

The study is a mixed-methods research with triangulation design in which both qualitative and quantitative data were used. The schematic plan of mixed method designs is provided by Creswell and Plano-Clark (Citation2011) as follows:

This research followed type “c” (Figure ) of their model according to which the phases of exploring the topic, identifying themes, designing instrument, and testing the instrument were conducted and the main emphasis was placed on qualitative data (Creswell & Plano-Clark, Citation2011). In doing the initial stages, both qualitative and quantitative data were considered to determine themes and then used the pre-test, treatment, post-test procedure (questionnaire and interview) to test the instrument and find answers to the research questions. The implementation stages of this study are summarized in table :

Figure 1. Design of Study- Derived from Prototypical Versions of Mixed Methods Research Designs (Creswell & Plano-Clark, Citation2011, p.69)

Table 1. Research Process Design

It was tried to use mixed-methods (QUAN-QUAL) both in the first and second phases in order to take advantages of the strengths of each method because according to Creswell (Citation2002) and Guest and Fleming (Citation2015), a study with mixed-method design supplies more comprehensive answers; Also, a research project in which different methods are integrated, is likely to have better quality and scope of results than single-method studies since such a method goes beyond the restrictions of a single approach (Gay & Airasian, Citation2003). Hanson et al. (Citation2005) claimed that application of the two types of information permit analysts to at the same time sum up outcomes from an example to a populace and to acquire a more profound comprehension of the phenomena under discussion. This is the same generalization of results from the sample to the population. The mixed-method design (QUAN + QUAL approach) was conducted in all stages of this present study i.e. in formulation of research questions, elaboration of the design, collection, demodulation and analysis of data, and interpretation of the findings.

To conduct the second phase of the study (i.e. second and third stages), the intact classes were selected since it was not possible to randomly assign the readers into three groups. The design of the study is schematically presented below. In this design, G1 stands for control group, G2 stands for the first experimental group, G3 stands for the second experimental group, “-” for “no treatment, “X1” for “the first treatment”, “X2” for “the second treatment”, T1 as pre-test, and T2 as post-test:

2.4. Procedure

First, the written informed consent was obtained from each participant before the start of the study. Then, a version of PET test was used to be assured of the homogeneity of the groups and then interview, document collection, and the questionnaires were used to explore the individuals’ opinions. It is worth mentioning that at this stage, to raise the awareness and recognition of the pilot group, the previously designed tools related to the concept were used. After transcribing interviews into written form, the data was analyzed via MaxQDA for primary coding, axial coding, and selective coding. As soon as the specifications are determined, treatment sessions were held in the form of sixteen-week training programs in which the experimental groups were introduced to the concepts and dimensions of critical thinking and critical reading (CR strategies introduced by Salisbury University, Citation2013) and performed reading comprehension assignments. In this phase of the study, the designed critical thinking survey (i.e. Critical Thinking Inventory) was used. Based on this, in the AWC group, students in groups of seven performed critical reading assignments using Hylighter, while in the QAR group, they relied on the teacher’s questions to find responses. Members of the control group were exposed to the conventional mainstream of teaching reading.

2.5. Data analysis

In the first phase, the data collected through the interviews, documents and questionnaires were coded and analyzed. Focusing on first research question, the MaxQDA software was used to find the most common features of critically-thinking EFL readers. Factors of the developed rating descriptor were assessed using SmartPLS in order to evaluate its validity (See, Mohammadi et al., Citation2022). In the next phases and after treatments, the performances of members in real groups were compared using ANOVA. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical issues and privacy restrictions.

3. Results

RQ 1. In a bid to explore the features of a critically-thinker EFL reader, the qualitative analysis followed by MaxQDA application was done. The qualitative analysis of the data resulted in extraction of six categories each with a number of sub-categories as shown in Table .

Table 2. Characteristics of a Critical Thinker EFL Reader

Figure and shows the tree diagram of the main categories, components or themes, and the sub-codes or measurement indicators gained from data analysis.

RQ 2. In order to address the second research question, both descriptive and inferential statistics were estimated. Leven’s test was used to investigate the equality of variances for the variable (See, Table ).

Table 3. Test of homogeneity of variances

The results of the Leven’s test, as a necessary prerequisite for an ANOVA test, represent that the variances of the groups are equal. Table represents the mean, standard deviation and confidence intervals for the dependents variable (critical thinking) for each separate group (Control, QAR and AWC), as well as when all of them (total) are combined (See, Table ).

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of the dependent variable (critical thinking)

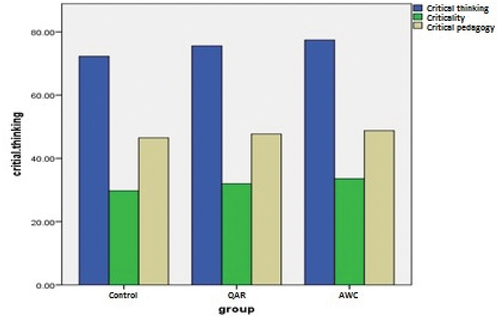

One can see from the descriptive table that the mean of the AWC group (M = 159.38) is higher than QAR group (M = 155.26) and Control group (M = 150.01). But in order to understand whether this difference is statistically significant, more detailed analysis was run. The chart shows that the performances of all three groups in the criticality and critical pedagogy sections are similar and it is necessary to determine any possible differences. The chart clearly shows that the AWC group outperformed the other two groups in critical thinking (See, Figure ).

ANOVA test results show that the F-value is 21.38 and sig. value is lower than .05, which means that there is a statistically significant difference in the mean performance of groups on critical thinking survey (See, Table ).

Table 5. ANOVA test results of groups’ performances on critical thinking survey

Therefore, it can be concluded that there was a statistically significant difference between groups as determined by one-way ANOVA (F (2, 151 = 21.387, p = .000)). However, to locate the differences, Multiple Comparisons test of the Tukey post hoc test results were used, too. A Tukey post hoc test revealed that the instructions implemented in groups caused differences based on which the AWC (mean = 159.38) significantly outperformed the QAR (mean = 155.26). [See, Table ].

Table 6. Multiple comparisons of the critical thinking as the dependent variable

RQ 3. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were estimated to find the answer to the third question. First, Leven’s test was used to investigate the equality of variances for the variable (See, Table ).

Table 7. Test of homogeneity of variances

The Leven’s test results show that the significance value is more than 0.05, meaning that there is a statistically significant difference in the mean of groups’ performances on critical reading test. Table represents the mean, standard deviation and confidence intervals for the dependents variable (critical thinking) for each separate group (Control, QAR and AWC), as well as when all of them (Total) are combined.

Table 8. Descriptive statistics of the dependent variable (critical reading)

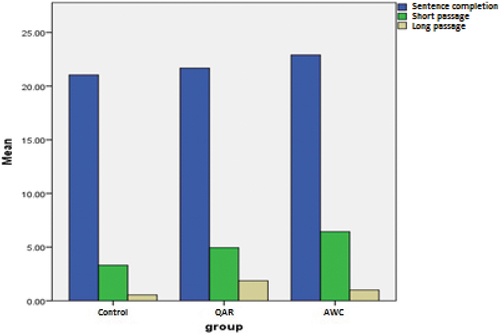

Figure shows how the three groups performed in critical reading (sentence completion, short passage, long passage). It shows that the performances of the three groups were different in different sections and it is necessary to examine these differences more closely. The chart clearly shows that their performances in the long passage and short passage sections are very weak and weak, respectively; this issue highlights the need for more attention and recognition of the factors affecting critical reading.

The ANOVA test result shows that there is a statistically significant difference between the group means. One can see that the F-value is 28.39 and sig.-value is lower than .05, which means that there is a statistically significant difference in the mean performance of groups on critical reading survey (See, Table ).

Table 9. ANOVA test results of groups’ performances on the critical reading tests

The results represent that there is a statistically significant difference in critical reading ability between the control group and QAR (p = .000), and control group and AWC (p = .000) as well as QAR and AWC (p = .035) as determined by one-way ANOVA test (F (2, 151 = 28.391, p = .000)). However, to locate the differences, Multiple Comparisons test of the Tukey post hoc test results were used based on which there was a significant difference between groups based on which QAR (M = 28.50) outperformed Control group (24.90); AWC (M = 30.34) outperformed Control group (24.90); and AWC (M = 30.34) outperformed QAR group (28.50; See, Table ).

Table 10. Multiple comparisons of the SAT as dependent variable

4. Discussion

First, the characteristics of a critically-thinker EFL learner were explored in the form of six categories each with a number of subcategories. Then, the results revealed that both the newly applied teaching methods were effective in developing critical thinking ability and critical reading, but AWC was more effective than QAR and control group instructions in developing critical thinking and reading comprehension.

The characteristics of a critical thinker EFL reader mentioned in this study are in line with the findings of Abedi (Citation2002), Kaewpet (Citation2018), Kember et al. (Citation2000), Pishghadam et al. (Citation2011), and Ricketts (Citation2003) while some of the factors introduced by Mann et al. (Citation1997) and Pishvaei and Kasaian (Citation2013) were not mentioned by the participants. Moreover, both classroom instructions were found to be effective in developing the traits which is in line with findings of Cox et al. (Citation2003), based on which the more knowledge of the pathway (i.e. instruction) results in a more desirable performance by learners.

The result of the analysis of the findings showed that there was a statistically significant difference in critical thinking and critical reading scores in favor of the post-test, representing that critical reading and thinking activities with a web-based collaborative approach have had a positive effect on the development of critical traits. This finding, in confirmation with the findings by Femilia (Citation2018), emphasizes the use of facilitative methods, especially the collaborative-interactive method. As it was mentioned by Haavind (Citation2006), Harden and Crosby (Citation2000), and Land et al. (Citation2007), this approach provided students with more time to analyze and reflect on texts. Land et al. (Citation2007) and Yang et al. (Citation2011), also represented that the social annotation, used as an asynchronous web-based collaborative technique, caused higher performance in both critical thinking and reading.

The study highlighted that the QAR method also promoted critical thinking and critical reading in learners which confirms the findings of Nugroho (Citation2012), Raphael et al. (Citation2006), and Raphael et al. (Citation2009), based on which such an explicit instruction supports reading and higher level thinking. In the same vein, Furtado and Pastell (Citation2012) stated that asking questions in the classroom strengthens learners’ participation, comprehension, and critical thinking skills. These results also confirm the findings of studies by Furtado and Pastell (Citation2012), Nugroho (Citation2012), and Untailawan (Citation2020) according to which the use of QAR method improves reading and thinking skills but the difference becomes apparent when the results of this method are compared with the AWC method.

Focusing on equality, diversity and inclusiveness of samples, it should be mentioned that one of the main axes of the present study is the issue of cultural differences and individual competences in understanding such aspects in the development of three-dimensional critical thinking. Therefore, efforts were made to fully respect the issue of cultural diversity and human conditions, and to fully consider ethnicity and culture, gender, age, social position, physical disability, mother tongue and dialect in designing, conducting and reporting the results. Specifically, in the first phase of the study, where the need to consider different attitudes and perspectives in the pilot group was quite noticeable, an attempt was made to pay close attention to such aspects, abilities and characteristics of participants. Moreover, in introducing the model and designing the survey, an attempt was made to prepare a standard questionnaire free of any cultural, ethnic, linguistic, and gender orientation and bias, and such attitude was considered in all stages of preparation and validation of the survey. However, due to the fact that this research was conducted on normal university students and in the implementation of its stages, various aspects of critical thinking such as creativity, deduction, induction, inferencing, recognizing author’s voice, innovation, etc. were addressed, therefore the issues of mental disability and young learners were not considered in this article and it is necessary to conduct a separate study to assess the introduced criteria or to identify and extract new criteria for people with mental disabilities.

Explicating the relationship between the findings of this study and previous research in various fields, it can be mentioned that the attitude taken in this study emphasizes all three dimensions of critical thinking i.e. personal, social, and cultural dimensions, and this is what has been referred to over the years in philosophical, psychological, and educational approaches separately. Therefore, it can be inferred that the results of this study are a turning point in reaching a consensus on critical thinking and providing a comprehensive definition for researchers and theorists of the three fields of science that have worked for years to reach it. In philosophical view of critical thinking, relying on the definition of this concept as formal logical thinking, it always focuses on the beliefs of Socrates and Aristotle and the importance of recognizing the requirements of such thinking. In contrast, psychological view considers critical thinking as a set of processes, skills, behaviors, and actions that help individuals to create an image and an understanding of issues and phenomena (Moon, Citation2008; Wang, Citation2017). Therefore, both the effect of internal and invisible factors and processes and their external manifestation are effective in cultivating critical thinking. Wang (Citation2017) also stated that the context and constraints that the environment and socio-professional conditions impose on an individual affect his/her critical thinking and its various components. This issue was clearly demonstrated during the interviews and data collection phases in this study, and it was found that various factors related to such impact place among the sub-components of two layers namely action and social cognition. Based on the opinions and results of previous studies (e.g., Davies, Citation2015; Davies & Barnett, Citation2015; Elder & Cosgrove, Citation2019) and the findings of this study, it can be concluded that to cultivate critical thinking, it is necessary to pay attention both to individual (first movement) and socio-cultural (second and third movements) factors. This study also revealed that -as acknowledged by Birjandi et al. (Citation2019), Davies (Citation2015), Etherington (Citation2021), and Ramírez-Verdugo and Márquez (Citation2021).—all the components of critical thinking are important and play an important role in the evolution process of this comprehensive concept.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study showed that the issue of theoretical implications can be viewed from two dimensions: the first dimension is the issue of providing a new framework in evaluating a critical reader with critical mind and the second dimension is the use of structural equation modeling in language studies. The first dimension represented that, as observed, this study provided a framework for assessing the critical reader who has critical thinking in the three main streams of individual skills, critical pedagogy and criticality. The results showed that in each of these three main streams, there are criteria that can be used to assess a learner’s abilities. Focusing on the second dimension, it should be mentioned that the validity of the criterion developed in this study was done by structural equation modeling, which is a new method and has a very limited history in language studies. It was observed that this method can be used to evaluate path analysis/regression, repeated measures analysis /latent changes modeling, and confirmatory factor analysis.

Figure depicts the critical thinking development framework presented in this study. As shown in this figure, critical thinking is developed in its early stages through cultivating individual skills such as argumentation, judgment, and disposition, and in its later stages, it should be evolved through applying the acquired skills and triggering the socio-cultural abilities. This is a confirmation of the theories of Davies (Citation2015) and Davies and Barnett (Citation2015), according to which a person first becomes a critical thinker by developing cognitive-individual skills and then becomes a critical being through acquiring and strengthening metacognitive and social skills.

Comparing the findings of this study with the model proposed by Krathwohl (Citation2002) shows that the components of the three-dimensional (3D) critical thinking cover well the components of Bloom’s modified taxonomy. In this framework, the components of the 3D-critical thinking, namely critical learning skills, criticality and critical pedagogy that are specified in the six levels of the pyramid are consistent with the components of Krathwohl’s model (marked on the right side of the framework).

The results and experiences obtained from the implementation of different stages in this study can clearly reveal the design of a mixed-method design. As it was mentioned by Tashakkori and Creswell (Citation2007) mixed methods design is a new method which needs more discussion and explication. Although data collection tools and data classification methods were selected to find the answers to the questions of this study, the general framework introduced in this study well reflects the realities of the method of conducting this type of study. In this study, various instruments were used to do triangulation of both qualitative and quantitative data which means that data sets from different tools were used to form the most complete picture of the issue.

Another implication of this study is the use of the developed tool; A tool that is not limited to the individual dimensions of learners’ characteristics, rather it considers various social, cultural, and educational dimensions. This tool is a proper criterion to be used by managers, educators, and policymakers in designing different educational objectives, curriculum, levels, and courses which can be used as follows:

Senior managers in ministries and policymakers can use the results of this research to plan for growth in the education system.

Using the results presented in this research, research centers can focus on identifying and introducing the factors affecting each of the sub-skills over time and in different societies.

Teachers may recognize and learn the methods of introducing and teaching each of these skills and subskills and abilities to students and promote a generation.

The teaching methods used in this study can also be used as clear and completely practical instructions for using the two methods of annotation and question-answer techniques in various classes.

This study has practical implications for readers as well. Readers may achieve higher levels of thinking by developing the competencies and skills introduced step by step and apply them in their daily readings. The following suggestions have been put forward:

One of the areas that should be studied is to examine the process of internalization and application of the skills introduced in this research in other courses and even in the individual and social life of individuals. Do people easily forget the acquired skills? How much do they use them? Is there any connection between individual tendencies and characteristics and using these skills? What effect does the field of study or occupation of individuals have on the application of each of the indicators?

This type of study can be done in the form of a longitudinal study to examine its long-term consequences and effects on participants and their performance and behavior. An additional area for further research includes examining people’s performance in different areas, behavioral and attitudinal changes, educational processes, changing timing and target population, and so on. This allows for a deeper exploration of the issues and findings raised in this study.

Future research may focus on the extent and manner of internalization of the introduced skills and the effectiveness of different internalization methods.

Further investigations are needed to assess course books and materials and even to design new materials to help both teachers and learners in gaining skills of critical thinking and reading.

In addition, there are other factors such as the optimal size of in-class groups, the type of participation, the difficulty level of the texts, the time spent asking and answering questions, etc., which require more careful consideration in future studies.

Finally, the educational view, trying to accept and rely on both mentioned views and find practical ways to implement recognized factors and improve individuals’ critical thinking, has desperately tried to find the proper teaching methods for introduced factors in different areas of education; Since, facing with constantly ever-changing educational, technological, and scientific conditions, it is forced to replicate and retest what has been measured. In explaining the educational perspective, it should be acknowledged that this view, trying to accept and rely on both previous views and finding practical ways to implement the introduced factors and promote critical thinking, has always focused on examining and finding appropriate instructional methods in various fields of education; And because of the ever-changing educational, technological, and scientific conditions and equipment, researchers are forced to repeat and re-test what has already been measured. And this study has been able to provide a comprehensive three-dimensional concept of critical thinking by considering all three perspectives, which in addition to theories and assumptions (philosophical perspective), and the evolution of different levels of critical thinking (psychological perspective), also focused on the comparison of instructions in teaching critical thinking (educational perspective).

It should not be forgotten that the purpose of learning such skills and traits is not to become proficient in each of them, but to raise individuals’ awareness of these skills and to grow each skill. Future research can also introduce the extent and manner of internalization of the introduced traits and the effectiveness of different internalization methods. The necessity of conducting intercultural studies, learners’ abilities and preferences, their mental-physical conditions, and the type and difficulty level of the texts with regard to the introduced criteria is felt.

Acknowledgements

Thank you for receiving our manuscript and considering it for review. We appreciate your time and look forward to your response. Sincerely, Mohammadi.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Moloud Mohammadi

Moloud Mohammadi is interested in educational topics, model simulation, media and technology in education, language acquisition, multilingualism, classroom leadership, and curriculum development.

Gholam-Reza Abbasian

Gholam-Reza Abbasian, is an associate professor of TEFL at Imam Ali University, Tehran, Iran, and a member of the Teaching English Language & Literature Society of Iran Board of Directors. He has presented at (inter)national conferences, authored good number of articles in scholarly journals and some books. He acts as an external examiner of PhD dissertations of Malaysian universities and as the internal manager of JOMM, and reviewer of Sage, FLA & GJER and some other journals.

Masood Siyyari

Masood Siyyari, an assistant professor of TEFL and applied linguistics at Science and Research Branch of Islamic Azad University, supervises MA theses and Ph.D. dissertations and teaches MA and Ph.D. courses. His main areas of research include language assessment and second language acquisition.

References

- Abedi, J. (2002). Standardized achievement tests and English language learners: Psychometrics issues. Educational Assessment, 8(3), 231–24. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326977EA0803_02

- Akbari, R. (2008). Transforming lives: Introducing critical pedagogy into ELT classrooms. ELT Journal, 62(3), 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/ELT/CCN025

- Alhujaylan, H. (2021). Academic vocabulary acquisition in web-based learning environment. Asian ESP Journal, 17(33), 32–57.

- Auzmendi, E., Villa, A., & Abedi, J. (1996). Reliability and validity of a newly constructed multiple choice creativity instrument. Creativity Research Journal, 9(1), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj0901_8

- Berardo, S. (2006). The use of authentic materials in the teaching of reading. The Reading Matrix, 6(2), 60–69.

- Birjandi, P., Bagheri, M. B., & Maftoon, P. (2019). Towards an operational definition of critical thinking. The Journal of English Language Pedagogy and Practice, 12(24), 17–40. https://doi.org/10.30495/JAL.2019.671910

- Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, handbook I: The cognitive domain. David McKay Co Inc.

- Brown, D. (2000). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (2nd) ed.). Longman.

- Burton, P. (2010). Creativity in Hong Kong schools. World Englishes, 29(4), 493–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2021.01677.x

- Callaghan, C. W. (2016). Critical theory and contemporary paradigm differentiation. Acta Commercii, 16(2), 59–99 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v16i2.421.

- Chen, Y. (2019). Developing students’ critical thinking and discourse level writing skill through teachers’ questions: A sociocultural approach. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 42(2), 141–162. https://doi.org/10.1515/CJAL-2019-0009

- Chou, P. T. M. (2011). The effects of vocabulary knowledge and background knowledge on reading comprehension of Taiwanese EFL students. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 8(1), 108–115.

- Cox, S. R., Freisner, D., & Khayum, M. (2003). Do reading skills courses help underprepared readers achieve academic success in college. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 33(2), 170–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2003.10850147

- Creswell, J. W. (2002). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Merrill Prentice Hall.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano-Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed-method research (2nd ed.). Sage Publication.

- Crosby, J. (1996). Learning in small groups. Medical Teacher, 18(3), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421599609034160

- Danvers, E. C. (2016). Criticality’s affective entanglements: Rethinking emotion and critical thinking in higher education. Gender and Education, 28(2), 282–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2015.1115469

- Davies, M. (2015). A model of critical thinking in higher education. In M. B. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (pp. 41–92). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12835-1_2

- Davies, M., & Barnett, R. (2015). Introduction. In M. Davies & R. Barnett (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of critical thinking in higher education (pp. 1–26). Palgrave McMillan.

- Dekker, T. J. (2020). Teaching critical thinking through engagement with multiplicity. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 37, 100701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100701

- Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Heath and Company.

- Elder, L., & Cosgrove, R. (2019). Critical societies: Thoughts from the past. The Foundation for Critical Thinking. Retrieved May 26, 2020, from http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/critical-societies-thoughts-from-thepast/762

- Ennir, R. (1991a). Critical thinking: A working concept. Teaching Philosophy, 14(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.5840/teachphil19911412

- Ennis, R. (1991). Critical Thinking: A Streamlined Conception. Teaching Philosophy, 14(1), 5–24. https://education.illinois.edu/docs/default-source/faculty-documents/robert-ennis/ennisstreamlinedconception_002.pdf

- Ennis, R. H. (1991). Critical thinking: A streamlined conception. Teaching Philosophy, 14(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.5840/teachphil19911412

- Ennis, R. H. (1996). Critical thinking dispositions: Their nature and assessability. Informal Logic, 18(2), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v18i2.2378

- Epstein, L. R., & Kernberger, C. (2006). The pocket guide to critical thinking (3rd). Thomson Wadsworth.

- Etherington, M. (2021). Smashing down “Old” ways of thinking: Uncritical critical thinking in teacher education. One World in Dialogue, 6(1), 26–38. https://ssc.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/OneWorldInDialogue/2021%20V6N1/Smashing%20Down%20Old%20Ways.pdf

- Facione, P. A. (1990). Executive Summary of Critical Thinking: A statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction. The California Academic Press.

- Femilia, P. S. (2018). Critical reading strategies employed by good critical readers of graduate students in ELT, State University of Malang. TEFLA Journal, 1(1), 30–34. https://doi.org/10.35747/tefla.v1i1.196

- Furtado, L., & Pastell, H. (2012). Question answer relationship strategy increases reading comprehension among kindergarten students. Applied Research on English Language, 1(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.22108/ARE.2012.15443

- Gabennesch, H. (2006). Critical thinking: What is it good for? Skeptical Inquirer, 30(2), 36–41. https://www.scicop.org/si/2006-02/thinking.html

- Gamboa-González, Á. M. (2017). Reading comprehension in an English as a foreign language setting: Teaching strategies for sixth graders based on the interactive model of reading. Folios, 45(1), 159–175. https://doi.org/10.17227/01234870.45folios159.175

- Gay, L. R., & Airasian, P. (2003). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and applications. Merrill.

- Geothals, S. M., Howard, A. R., & Sanders, M. M. (2004). Student teaching: A process approach to reflective practice. A guide for pre-service and in-service teacher (2nd) ed.). Pearson Education.

- Glaser, E. M. (1941). . In An experiment in the development of critical thinking. J. J. Little and Ives Company .

- Guest, G., & Fleming, P. J. (2015). Mixed methods research. In G. Guest & E. Namey (Eds.), Public Health Research Methods (pp. 581–610). Sage.

- Haavind, S. (2006). Key factors of online course design and instructor facilitation that enhance collaborative dialogue among learners. Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=50868d5ac3dfaf21a793d5b4b0d75a0bb47eed15

- Habbash, M. (2021). Using internet-based reading activities to enhance the face-to-face teaching of reading in community college at the university of Tabuk. Asian EFL Journal, 28(3), 10–22. https://www.asian-efl-journal.com/monthly-editions-new/2021-monthly-edition/volume-28-issue-3-2-june-2021/index.htm

- Hall, L., & Piazza, S. (2008). Critically reading texts: What students do and how teachers can help. Reading Teacher, 62(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.62.1.4

- Halvorsen, A. (2005). Incorporating critical thinking skills development into ESL/EFL courses. The Internet TESL Journal, XI(3), 1–6. https://iteslj.org/Techniques/Halvorsen-CriticalThinking.html

- Hanson, W., Creswell, J., Plano Clark, V., Petska, K., & Creswell, J. (2005). Mixed methods research designs in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.224

- Harden, R. M., & Crosby, J. (2000). AMEE education guide no. 20: The good teacher is more than a lecturer-the twelve roles of the teacher. Medical Teacher, 22(4), 334–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/014215900409429

- Holbeck, R., & Hartman, J. (2018). Efficient strategies for maximizing online student satisfaction: Applying technologies to increase cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence. Journal of Educators Online, 15(3), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.9743/jeo.2018.15.3.6

- Ilyas, H. P. (2018). Indonesian EFL teachers’ conceptions of critical thinking. Journal of ELT Research, 3(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.22236/JER_Vol3Issue1pp29-37

- Imperio, A., Staarman, J. K., & Basso, D. (2020). Relevance of the socio-cultural perspective in the discussion about critical thinking. Journal of Theories and Research in Education, 15(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.6092/.1970-2221/9882

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2008). Social Interdependence theory and cooperative learning: The teacher’s role. In M. Gillies, A. Ashman, & J. Terwel (Eds.), The teacher’s role in implementing cooperative learning in the classroom (pp. 9–37). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-70892-8_1

- Kaewpet, C. (2018). Quality of argumentation models. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 8(9), 1105–1113. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0809.01

- Kember, D., Doris, Y., Leung, A. J., Loke, A. Y., McKay, J., Sinclair, K., Tse, H., Webb, C., Wong, F. K. Y., Wong, M., & Yeung, E. (2000). Development of a questionnaire to measure the level of reflective thinking. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 25(4), 382–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/713611442

- Kivunja, C., & Kuyini, A. (2017). Understanding and applying research paradigms in educational contexts. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(5), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v6n5p26

- Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 212–218. https://www.depauw.edu/files/resources/krathwohl.pdf

- Land, S. M., Choi, I., & Ge, X. (2007). Scaffolding online discussions to promote reflection and revision of understanding. International Journal of Instructional Media, 34(4), 409–418.

- Lewis, C. (2000). Critical issues: Limits of identification: The personal, pleasurable and critical reader response. Journal of Literacy Research, 32(2), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/10862960009548076

- Lou, Y., Abrami, P., & D’Apollonia, S. (2001). Small group and individual learning with technology: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 71(3), 449–521. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543071003449

- Loving, G. (1993). Competence validation and cognitive flexibility: A theoretical model grounded in nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education, 32(9), 415–421. https://doi.org/10.3928/0148-4834-19931101-07

- Mace, G. M. (2005). An index of intactness. Nature, 434(7029), 32–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/434032a

- Malterud, M., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- Mann, L., Burnett, P., Radford, M., & Ford, S. (1997). The Melbourne decision making questionnaire: An instrument for measuring patterns for coping with decisional conflict. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 10(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0771(199703)10:1<1::AID-BDM242>3.0.CO;2-X

- Meneses, L. F. S. (2020). Critical thinking perspectives across contexts and curricula: Dominant, neglected, and complementing dimensions. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 35, 100610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2019.100610

- Mertens, D. M. (2010). Philosophy in mixed methods teaching: The transformative paradigm as illustration. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 4(9), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.5172/mra.2010.4.1.009

- Mohammadi, M., Abbasian, G. R., & Siyyari, M. (2022). Adaptation and validation of a critical thinking scale to measure 3d critical thinking ability of EFL readers. Language Testing in Asia, 12(24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-022-00173-6

- Moon, J. (2008). Critical thinking: An exploration of theory and practice. Routledge.

- Nugroho, D. A. (2012). The effectiveness of Question and Answer Relationship (QAR) method in teaching reading viewed from students’ intelligence: An experimental study in the Second Year of SMPN 2 Madiun in the Academic Year of 2011/2012. [Unpublished Master’s Thesis], University of Surakarta.

- O’Neil, H. F., Abedi, J., & Spielberg, C. D. (1994). The measurement and teaching of creativity. In H. F. O’Neil & M. Drillings (Eds.), Motivation: theory and research (pp. 245–264). Erlbaum.

- Pabel, A., Pryce, J., & Anderson, A. (2021). Embarking on the paradigm journey. In A. Pabel, J. Pryce, & A. Anderson (Eds.), Research paradigm considerations for emerging scholars (pp. 1–12). Channel View Publications.

- Padilla, A. M., & Perez, W. (2003). Acculturation, social perspective, and social cognition: A new perspective. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25(1), 35–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986303251694

- Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2006). Critical thinking: Tools for taking charge of your learning and your life. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Paulsen, M. B. (2015). Higher education: Handbook of theory and research. Springer.

- Peng, S. G. R., Hoon, T. L., Khoo, S. F., & Joseph, I. M. (2007). The impact of Question-Answer-Relationship on reading comprehension. Pie Chun public school and Marymount convent. Ministry of education.

- Pennycook, A. (1990). Critical Pedagogy and Second Language Education. System, 18(3), 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/0346-251X(90)90003-N

- Pishghadam, R., Noghani, M., & Zabihi, R. (2011). The Construct Validation of a Questionnaire of Social and Cultural Capital. English Language Teaching, 4(4), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n4p195

- Pishvaei, V., & Kasaian, S. A. (2013). Design, construction, and validation of a critical pedagogy attitude questionnaire in Iran. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences, 2(2), 59–74.

- Ramírez-Verdugo, M. D., & Márquez, E. (2021). A sociocultural study on English learners’ critical thinking skills and competence. In E. Hanci-Azizoglu & M. Alawdat (Eds.), Rhetoric and sociolinguistics in times of global crisis (pp. 79–99). IGI Global.

- Raphael, T. E., George, M., Weber, C. M., & Nies, A. (2009). Approaches to teaching reading comprehension. In S. E. Israel & G. G. Duffy (Eds.), Handbook of research on reading comprehension (pp. 449–469). Guilford Press.

- Raphael, T. E., Highfield, K., & Au, K. H. (2006). QAR now: A powerful and practical framework that develops comprehension and high-level thinking in all students. Scholastic, Inc.

- Reed, J. H. (1998). Effect of a model for critical thinking on student achievement in primary source document analysis and interpretation, argumentative reasoning, critical thinking dispositions, and history content in a community college history course. [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation]. University of South.

- Reznitskaya, A., & Anderson, R. C. (2002). The argument schema and learning to reason. In C. C. Block & M. Pressley (Eds.), Comprehension instruction: Research-based best practices (pp.319-334). Guilford.

- Ricketts, J. C. (2003). The Efficacy of Leadership Development, Critical Thinking Dispositions, and Students Academic Performance on the Critical Thinking Skills of Selected Youth Leaders. [unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Florida.

- Salisbury University. (2013). 7 critical reading strategies. http://www.salisbury.edu

- Schoeman, S., & Mabunda, P. L. (2011). Teaching practice and the personal and socio-professional development of prospective teachers. South African Journal of Education, 32(3), 240–254. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v32n3a581

- Simonton, D. K. (2006). Creativity around the world in 80 ways … but with one destination. In J. C. Kaufman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The international Handbook of Creativity (pp. 490–496). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511818240.017

- Sinaga, P., & Feranie, S. (2017). Enhancing critical thinking skills and writing skills through the variation in non-traditional writing task. International Journal of Instruction, 10(2), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2017.1025a

- Stanton, A. D., & Stanton, W. W. (2017). Using journaling to enhance learning and critical thinking in a retailing course. Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education, 25, 32–36.

- Su, A. Y. S., Yang, S. J. H., Hwang, W., & Zhang, J. (2010). A web 2.0-based collaborative annotation system for enhancing knowledge sharing in collaborative learning environments. Computers & Education, 55(2), 752–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.03.008

- Tashakkori, A., & Creswell, J. W. (2007). Exploring the nature of research questions in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Method Research, 1(3), 207–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689807302

- Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Tishman, S., & Andrade, A. (1996). Thinking dispositions: A review of current theories, practices, and issues. Harvard University.

- Untailawan, F. (2020). Improving students’ reading comprehension and critical thinking skills through the implementation of qar strategy at SMA PGRI dobo. Soshum: Jurnal Sosial Dan Humaniora, 10(1), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.31940/soshum.v10i1.1721

- Wang, S. (2017). An exploration into research on critical thinking and its cultivation: An overview. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 7(12), 1266–1280. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0712.14

- Weiner Green, S., & Weiner, M. (2012). Barron’s new SAT reading workbook (14th) ed.). Barron’s Educational Series.

- Wheeler, A., Yeomans, P., & Wheeler, D. (2008). The good, the bad and the Wiki: Evaluating student-generated content for collaborative learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(6), 987–995. https://odi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00799.x

- Wilson, K. (2016). Critical reading, critical thinking: Delicate scaffolding in English for Academic Purposes (EAP). Thinking Skills and Creativity, 22, 256–265.

- Yang, H. (2017). A research on the effective questioning strategies in Class. Science Journal of Education, 5(4), 158–163. https://doi.org/10.11648/J.SJEDU.20170504.16

- Yang, S. J., Zhang, J., Su, A. Y., & Tsai, J. J. (2011). A collaborative multimedia annotation tool for enhancing knowledge sharing in CSCL. Interactive Learning Environments, 19(1), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2011.528881

- Zembylas, M. (2022). Revisiting the notion of critical thinking in higher education: Theorizing the thinking-feeling entanglement using affect theory. Teaching in Higher Education, Teaching in Higher Education., 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2022.2078961