Abstract

Concern for the environment is widespread and consumers generally hold favorable values toward green consumption; however, they often struggle to translate these values into actual green consumption behaviors. This so-called “green gap” has attracted much research interest in recent years, yet questions remain regarding the factors that may influence it and what form this influence takes. Taking the cognitive view in studying green consumption, we seek to shed light on the green gap by empirically testing the roles of risk aversion and subjective knowledge as potential moderators of the green value-action disparity. Proposing a moderated moderation model, we additionally explore the categorical interaction effect of gender differences with risk aversion and subjective knowledge in predicting green purchase behaviors. Using structured survey data (N = 328), we demonstrate that consumers lower in general risk aversion and higher in green subjective knowledge have greater consistency between their values and behaviors in the green consumption context. Further, we reveal a conditional interaction effect of gender in which women were less risk-averse and more knowledgeable than men, resulting in greater green value-behavior consistency. Our study contributes to the growing body of research on sustainable consumption by offering psychographic explanations for the inconsistency between what consumers say and do when it comes to green purchasing. Implications of this study encourage consumer researchers, global managers, and public policy makers, when developing green marketing programs or when seeking to strengthen the green value-action relationship in general, to consider how risk aversion and subjective knowledge may interact with gender differences.

Introduction

The culture of consumption in which we live is inextricably linked to the sustainability phenomenon: existing unsustainable consumption modes and their vicious effects on the global economy and environment stand as formidable hurdles facing humankind (Peattie, Citation2010). As an antidote to this looming crisis, fostering green consumption is anticipated to reverse environmental deterioration to a certain degree and help to mitigate critical overexploitation of natural resources (Trudel, Citation2018). Marketers are rallying to this cause: green consumption has become a mainstream practical tool for businesses in the process of positioning and communicating their competitive strategies over time (Naciti, Citation2019). Green consumption has also emerged as a topic of high interest among consumer researchers who have attempted to understand green values and behaviors of individuals by exploring how they are shaped by diverse sociodemographic (Casalegno et al., Citation2022), psychographic (Park and Lin, Citation2020), situational (Nguyen et al., Citation2019), cultural (Halder et al., Citation2020), and social factors (Essiz and Mandrik, Citation2022). Nevertheless, research on green consumption values and behaviors is equivocal and shows the link between values and behaviors often to be tenuous when it comes to consuming sustainably.

A recurring theme in this research stream is the green attitude-behavior gap (i.e., value-action gap) – that is, the environmental value-behavior inconsistency – revealed when “strongly held pro-environmental values frequently fail to translate into green purchasing action or other pro-environmental behaviors in practice” (see Peattie, Citation2010, p. 213 for the conceptualization; ElHaffar et al., Citation2020 for the narrative review). Empirical evidence for this green gap has been reported steadily in various countries, including but not limited to the UK (Young et al., Citation2009), US (Farjam et al., Citation2019), Canada (Durif et al., Citation2012), Hong Kong (Lee, Citation2008), India (Chatterjee et al., Citation2021), Vietnam (Nguyen et al., Citation2019), and in various contexts such as organic food consumption (Schäufele and Janssen, Citation2021), recycled and sustainable fashion products (Park and Lin, Citation2020), sustainable transportation (Haider et al., Citation2019), and residential energy consumption (Zhang et al., Citation2021), among others.

This green gap between what consumers say and do is arguably one of the greatest challenge for marketers, public policymakers, and nonprofit organizations working to promote the United Nations’ 2030 sustainable development goals (SDGs), in particular goal number 12 which concerns sustainable consumption and production (United Nations, Citation2015). To encourage development of green consumption habits and safeguard the viability of SDG 12, researchers must understand what motivates people to purchase green products, which also may help to elucidate the moderating mechanisms underlying the green gap (ElHaffar et al., Citation2020; Chaihanchanchai and Anantachart, Citation2022). Consequently, this research is needed to detect prospective moderators that may help explain the (in)consistency between values and behaviors in the consumption of green products. Ironically, only 51% of global consumers express interest in sustainable offerings, while 68% of them expect companies to solve sustainability issues; and these consumers are deterred from purchasing green products predominantly by psychographic causes (EY Future Consumer Index, Citation2021). Thus, providing a clear understanding of the interplay between values and psychographic moderators in predicting green purchase behavior is crucial for global marketers to create effective strategies that encourage growth of green products and pave the way for a more sustainable future.

At this juncture, past research attempted to profile the green gap by mostly exploring moderating roles of situational or contextual factors, including product availability and perceived consumer effectiveness (Nguyen et al., Citation2019), product category involvement and sustainability involvement levels (Frank and Brock, Citation2018), price framing (Weisstein et al., Citation2014), social norms and shopping modes (Casais and Faria, Citation2022), and pro-social status perceptions (Zabkar and Hosta, Citation2013), among others. Despite the importance of an individual’s psychographic characteristics as the main determinant of actual green behaviors (Peattie, Citation2010; Trudel, Citation2018), and assertion that the green gap can be better understood by investigating demographic and individual differences (Chaihanchanchai and Anantachart, Citation2022), research on potential moderating roles of psychographic factors affecting the green value-action relationship is almost absent. Two important but neglected personal factors in particular are pointed out by ElHaffar et al. (Citation2020, p. 15) in the following suggestion: “future empirical research should understand the roles of risk-aversion and subjective knowledge to provide a more holistic overview of the green gap.” But why are these factors so crucial for understanding the green gap?

Like other consumption activities, green consumption choices involve financial, social, performance, physical, and psychological risks (Kaplan, Citation1974; Saari et al., Citation2021). Given that green consumption is yet somewhat esoteric in nature, arguably it may be associated with higher levels of perceived risk and uncertainty, particularly in relation to such issues as quality, trust, value, perceived unclearness, and functionality judgments (Durif et al., Citation2012). The heightened role of risk perception in green consumption elevates the importance of understanding personal factors related to risk, such as the concept of risk aversion, to shed light on the green gap. In a similar vein, where green consumption is concerned, subjective knowledge may also be an important underlying mechanism influencing the green gap as it either directly or indirectly affects green purchase involvement (Pagiaslis and Krontalis, Citation2014) and risk decisions (Saari et al., Citation2021). Finally, gender may be another factor worthy of investigation: as a result of different routes of socialization (Zelezny et al., Citation2000), male and female consumers often espouse different levels of green values (Bulut et al., Citation2017) and behaviors (Mostafa, Citation2007), which may lead to differences in how they relate to green purchases and concomitantly the green gap. Following this line of reasoning and recognizing the gaps in research investigating the nexus of risk aversion, subjective knowledge, and gender in the green domain, this research addresses these factors. Specifically, this investigation is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1. How do general risk aversion (GRA) and green subjective knowledge (GSK) influence the relationship between green consumption values (GCVs) and green purchase behaviors (GPBs)?

RQ2. What is the role of gender differences in the above construct relationships?

This study makes several theoretical and practical contributions to our understanding of green consumption. Theoretically, corroborating the arguments in the green value-action gap and building on the empirical context of Turkey, we propose a novel research model that helps to explain this ongoing theoretical inconsistency – the green gap – through two new moderating psychographic variables and reaffirm the prominent role of green values in explaining purchase behaviors. From a micro-level perspective, our research contributes to the stream of previous research that examines the role of gender in green consumption by originally quantifying boundary distinctions between men and women in the green value-behavior link. In terms of practical contributions, this study provides useful insights for global practicing managers for fine-tuning their green marketing strategies, including enhanced understanding of green brand positioning and better management of the communication programs for green brands through segmentation on the basis of risk aversion, subjective knowledge, and gender. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: first, relevant literature is reviewed to provide the conceptual background and justification for our research hypotheses and propositions. Next, the method and measures of the empirical study are explained, followed by a discussion of the main findings and their implications. The paper concludes by discussing limitations and suggesting further research caveats.

Theoretical background and conceptual development

Green consumption and the green gap: Values and behaviors

Values form a vital part of an individual’s self-perception and have long been regarded as central explanatory factors behind behaviors (Rokeach, Citation1973), operating as guiding principles and justifying the likelihood of engaging in certain actions (Schwartz, Citation2010), such as a consumer’s purchasing decisions (Schuitema and De Groot, Citation2015). Given that values may lessen or enhance the likelihood of performing specific behaviors, value-consistent behavior should be explored through area-specific consumption domains (Haws et al., Citation2014) – green consumption in the present study. In the green domain, former research emphasized the role of values in guiding, influencing, and moderating consumers’ behaviors (e.g., Grønhøj and Thøgersen, Citation2009; Haws et al., Citation2014; Bailey et al., Citation2018; Chatterjee et al., Citation2021). This research stream underscores a strong positive relationship between green values and behaviors such that when consumers possess a high level of green values, they are more likely to be concerned for the environment and reflect this concern in their consumption choices, becoming judicious users of physical resources. In fact, Haws et al. (Citation2014, p. 337), defined green consumption values as “individuals’ tendency to express the amount of their environmental commitment on their consumption behaviors.” However, it is evident as well that values are not the sole determinant of environmentally friendly behaviors; that is, a positive association may hold true to some degree yet in practice the green gap still may loom large. In other words, not all positive values directly translate into actions, and consumers may say one thing, yet do another, failing to follow through in actual green consumption behaviors (ElHaffar et al., Citation2020). In parallel with early theoretical assumptions, we expect to see a positive correlation between green values and behaviors, yet our concern is for exceptions that may occur – namely, the green gap.

Turning toward behaviors, the concept of green consumption behaviors has been defined as a “distinct set of consumer acts that are strongly influenced by concern for social, environmental, and economic considerations” (Luchs and Mooradian, Citation2012, p. 129). When consumers engage in green consumption behaviors, they usually avoid purchasing products that cause harm to the environment and seek to consume goods that enhance the welfare of society at micro and macro levels. Previous research has investigated green behaviors under a wide range of categories, including energy and water-saving (Gilg and Barr, Citation2006), recycling and donation (Ha-Brookshire and Hodges, Citation2009), sustainable transportation (Haider et al., Citation2019), sustainable fashion choices (Park and Lin, Citation2020), sustainable food consumption and product choices (Frank and Brock, Citation2018), among others. While exploring this broad domain of green consumption, researchers have attempted to grasp the roles of numerous moderating factors affecting the intention-behavior or value-action relationship. provides a snapshot of this former research. As can be seen from , most prior work examined either situational or contextual moderators, pointing to a critical need to understand potential moderating roles of psychographic variables, and supporting our current focus on general risk aversion, green subjective knowledge, and gender differences. Another gap evident from is that past research included values and behaviors limited in scope to focus only on specific – typically highly visible – environmental practices (e.g., organic food purchase, energy saving measures, recycling behaviors). Against this backdrop, we note that our treatment of green consumption is broader in scope and embraces the “Three Pillars” (i.e., environmental, social, economic) of the sustainability concept (United Nations, Citation2002), with special weight on environmental sustainability.

Table 1. Snapshot of green consumer research: Former moderating variables tackling the green value-action gap.

A final theoretical point to note is that green consumption studies usually take a “cognitive view” in which consumer behavior is based on information-seeking and mostly directed by psychographic characteristics and specific goals (Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Saari et al., Citation2021; Chatterjee et al., Citation2021). Under this cognitive paradigm, most researchers have adopted the theory of planned behavior (TPB, Ajzen, Citation1991) to study the green gap phenomenon. However, other social-psychological frameworks, more specifically, the value basis theory of Stern and Dietz (Citation1994) and the value-belief-norm theory (VBN) of environmental activism (Stern et al., Citation1999) also have been highlighted as useful rational-cognitive paradigms in explaining green value-action discrepancy (Elhaffar et al., Citation2020). Both theories posit that a general set of green values predict green behaviors of consumers and both are open to the inclusion of additional psychographic predictors, such as habits and routines, as green values are believed to interact with such internal factors of consumers. Building on these basic theoretical foundations, we note recent work that has highlighted the role of knowledge, awareness of environmental issues, and risk perception as having an important influence on pro-environmental behaviors (Saari et al., Citation2021); however these factors have not been explored as moderators of the green gap. Adopting the perspective of the aforementioned theoretical paradigms and taking the “cognitive view” in studying green consumer behavior, we next discuss potential moderators of the green gap.

Role of general risk aversion in green consumption

A choice between two or more options is recognized as a central problem in consumer behavior, as the outcome of choice is often ambiguous; hence, consumers must cope with the uncertainty and risk that choices entail (Taylor, Citation1974; He et al., Citation2022). Addressing risk, Bauer (Citation1960) originally introduced to consumer behavior research the perceived risk concept, conceptualized as the perception of uncertainty in consumers’ decision-making processes and the consequences of making a poor choice. Weber and Bottom (Citation1989) categorized consumers as (1) risk-averse, (2) risk-seeking, and (3) risk-neutral by examining their choice behaviors, illustrating how consumers’ predisposition toward risk may differ in regard to the total risk they are willing to undertake in particular circumstances. Risk aversion has been primarily defined as a “decision maker’s preference for a guaranteed outcome over a probabilistic one having an equal expected value” (Qualls and Puto, Citation1989, p. 180). However, this definition is based on revealed preferences for gambles and is methodologically constrained. A more general approach is the concept of general risk aversion, defined as “the degree of negative attitude towards risk due to outcome uncertainty” (Mandrik and Bao, Citation2005, p. 533). Thus, it is not bound by the perceived negative consequences (Bauer, Citation1960) which may depend on a particular domain and, in fact, has been shown to affect consumer decision-making in a variety of contexts. To that end, general risk aversion has been found in numerous studies to affect many behaviors that are linked to values, for example preferences for gambles (Pontes and Williams, Citation2021), investment decisions (Aren and Hamamci, Citation2020), online shopping (Kim and Byramjee, Citation2013), and brand choices (Matzler et al., Citation2008), among others. Therefore, it is plausible that a consumer’s degree of general risk aversion also may be related to their likelihood to engage in green purchasing activities.

Risk aversion affects consumers in many ways. Consumers who have a higher degree of risk aversion tend to give more importance to perceived quality and transparency in their consumption behaviors (Li and Qi, Citation2021). Similarly, it is understood that high-risk-averse consumers tend to avoid unexpected financial losses and, as a result, they tend to purchase well-known brands rather than buying unfamiliar new brands. In contrast, low-risk-averse consumers (i.e., risk-tolerant consumers) feel more excited and less threatened while buying new or innovative products from unknown brands since they feel more confident in their decisions (Matzler et al., Citation2008). Low-risk-averse consumers also may have better consumption knowledge and may be willing to engage more frequently in shopping activities which provide opportunities to explore new brands and concepts (Bao et al., Citation2003). Owing to the esoteric nature of green consumption and based on this past research on choices involving risk, it is arguable that low-risk-averse consumers may experience less uncertainty and be willing to undertake more risk when it comes to purchasing and using green products. Given that green products entail higher perceived risks compared to conventional offerings (Durif et al., Citation2012; Sun et al., Citation2021), it seems reasonable that consumers with higher general risk aversion, when faced with a green purchase decision, should experience greater uncertainty and a hesitancy to choose green products, thereby enlarging the green value-action gap.

In fact, there is ample evidence that risk aversion may serve to moderate the relationships among a variety of factors related to consumption, particularly where purchase decisions are involved. For example, risk aversion moderates the relationship between online purchasing and the value perceived by consumers (Kim and Byramjee, Citation2013), customer satisfaction and loyalty intentions (Matzler et al., Citation2008), and product incongruity and evaluations (Gürhan-Canli and Batra, Citation2004). Although the effects of risk aversion are fairly well-documented across many consumption domains and behaviors, the explicit moderating role and direct effects of this construct have not been addressed in the context of sustainable consumption, particularly in relation to green consumption values and purchase decisions. However, related research exists regarding the effect of perceived risk on environmental concern and protection (Saari et al., Citation2021). Most recently, studies reveal that perceived risk is an important precursor for behavioral change, and it may play a role in value-action continuity in the context of specific green domains such as bioenergy consumption, green vehicle adoption, and climate change mitigation practices, since consumers often make decisions based on predetermined and exogenous risk factors (Maartensson and Loi, Citation2022; He et al., Citation2022; Vafaei-Zadeh et al., Citation2022). These recent domain-specific findings suggest that risk aversion traits of consumers may illuminate our understanding of the green gap.

In sum, the various facets of perceived risk (e.g., social, psychological, financial, performance, physical, or functional) and ambiguities (e.g., price/quality dilemmas, uncertainty of utility and value judgments) inherent in green consumption situations (Durif et al., Citation2012; Sharma, Citation2021; Vafaei-Zadeh et al., Citation2022; Maartensson and Loi, Citation2022) should predispose consumers with a higher degree of general risk aversion to be less willing to translate their green values into actual green purchase behaviors, enlarging the green gap. Based on the preceding review, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1. General risk aversion is negatively related to green purchase behaviors.

H2. General risk aversion negatively moderates the relationship between green consumption values and green purchase behaviors, such that higher general risk aversion leads to a weaker relationship between green values and green behaviors.

Role of subjective knowledge in green consumption

At the individual level, green environmental knowledge is understood to be a vital element of the green consumption process, directly or indirectly shaping beliefs, values, and attitudes, and aiding consumers to make more informed purchase decisions (Sharma, Citation2021; Chaihanchanchai and Anantachart, Citation2022). This implies that the level of knowledge consumers possess about specific green behaviors is instrumental to forming their attitudes and subsequent behaviors toward associated objects, such as when making choices involving green products. Prior research depicts green knowledge as facts, concepts, relationships, and information related to the economic, social, and ecological effects of sustainability (Berki-Kiss and Menrad Citation2022; Pagiaslis and Krontalis, Citation2014; Suki, Citation2016), and classifies it as either (1) abstract or (2) concrete knowledge. Abstract knowledge is subjective, that is, self-perceived or self-rated (Ellen, Citation1994; Flynn and Goldsmith, Citation1999), while concrete knowledge is objective, referring to what an individual actually knows about a particular topic (Park et al., Citation1994; Lee, Citation2010). The present study focuses only on subjective knowledge – what consumers think they know of topics related to green consumption – because it is often what consumers think they know, and not what they actually know, that guides their choices (e.g., Ellen, Citation1994; Raju et al., Citation1995; Berki-Kiss and Menrad Citation2022).

The subjective knowledge construct encompasses issues such as environmental problems and solutions, the benefits or costs associated with green products, and procedural knowledge, among others (Khare et al., Citation2020). Subjective knowledge has been positively associated with environmental beliefs (Pagiaslis and Krontalis, Citation2014), intentions (Saari et al., Citation2021), a variety of green consumer behaviors (Essiz and Mandrik, Citation2022), and with specific green practices linked to organic food and clothing consumption (e.g., Aertsens et al., Citation2011; Pieniak et al., Citation2010; Khare et al., Citation2020; Abrar et al., Citation2021). Past research suggests that a higher level of green subjective knowledge leads to stronger pro-environmental attitudes and purchase intentions because it may enhance the self-confidence of consumers in the decision-making process (Chaihanchanchai and Anantachart, Citation2022; Essiz and Mandrik, Citation2022). An implication of this finding is that consumers who do not believe they possess the requisite knowledge to understand characteristics of green products or eco-labels may be hesitant to purchase such products, underscoring the role of subjective knowledge in seeing a green purchase through to completion.

Building on this past research, the well-documented main effect of subjective knowledge on green purchase behaviors points to its potential as a moderator of the green value-action relationship. In the present study, our sample group should be expected to possess some degree of knowledge in the sphere of green consumption, considering the wide availability of information sources (e.g., the Internet, seminars, courses, clubs, and voluntary initiatives). Subjects with higher knowledge should be more willing to engage in green consumption as they may easily access and activate information stored in their memory (e.g., Berki-Kiss and Menrad Citation2022), thereby more readily translating their existing green values into purchase behaviors. Similarly, higher-knowledge subjects may be more able to cope with various components of risk related to green consumption (Saari et al., Citation2021). To the degree that high knowledge consumers are better able to understand and cope with risks inherent in making purchase decisions, the consistency between their green values and actions should be strengthened. For these reasons, we suggest that green subjective knowledge should interact with green values and general risk aversion in predicting green purchase behaviors. Essentially, consumers with higher subjective knowledge should be more inclined to translate their green values into actual usage of green products, reducing the green value-action gap. In light of the above discussion, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3. Green subjective knowledge is positively related to green purchase behaviors.

H4. Green subjective knowledge positively moderates the relationship between green consumption values and green purchase behaviors, such that higher subjective knowledge leads to a stronger relationship between values and behaviors.

Gender differences in green consumption

Broadly speaking, early literature recommends using sociodemographic variables principally as categorical factors for better understanding motives behind the development of green consumption habits (Costa Pinto et al., Citation2014; Clark et al., Citation2019), and we echo this sentiment. Given that prior research investigating the green value-action relationship has largely neglected to conceptualize the role of gender, and in light of reported inconsistencies between men and women, we sought to analyze how gender as a categorical variable may interact with our two moderators in predicting green behaviors. Gender is an important element influencing behavior of consumers in a variety of general consumption domains and specific situations (e.g., Kreczmańska-Gigol and Gigol, Citation2022; Phillips and Englis, Citation2022). For instance, while processing information about products or elaborating particular messages from advertisements, men and women may display different levels of receptivity to decision-making inputs, resulting in behavioral differences (Tewari et al., Citation2022). This seems to hold true when it comes to green consumption: gender plays an important role in predicting green consumer behaviors (Costa Pinto et al., Citation2014; Brough et al., Citation2016; Kreczmańska-Gigol and Gigol, Citation2022; Phillips and Englis, Citation2022); however, empirical support is somewhat inconsistent.

Regarding green consumption knowledge and behaviors, research is ambivalent; some research shows moderate support for gender differences (Costa Pinto et al., Citation2014; Mostafa, Citation2007; Pagiaslis and Krontalis, Citation2014), while others find no such differences (Bailey et al., Citation2018; Claudy et al., Citation2013; Finisterra do Paço and Reis, Citation2012). Some research shows that men are more knowledgeable (Mostafa, Citation2007) while other research indicates that women are (Bulut et al., Citation2017), leading to an enduring green gap gender debate (Mohai, Citation1992; Clark et al., Citation2019). Tan et al. (Citation2022) argue that female consumers may hold higher level of green consumption values as part of their sustainable resale behavior on sharing economy platforms. Most recently, Phillips and Englis (Citation2022) add to the ongoing dialog by disentangling the effects of gender and gender identity on green consumption attitudes and behaviors. Intriguingly, these authors argue that green consumption is a gender-neutral phenomenon in which androgynous consumers – those who hold both masculine and feminine traits – exhibit the strongest set of green attitudes and behaviors. In sum, while no consensus has yet emerged regarding gender differences, it is apparent that gender does influence the levels of both subjective knowledge and green values (e.g., Dhir et al., Citation2021; Tan et al., Citation2022), which points to probable gender differences in the green value-behavior link.

Regarding risk-taking behaviors when engaging in green consumption, gender differences have been largely overlooked. However, it is recognized that green products entail higher perceived risks compared to their conventional counterparts, especially when it comes to utility and value judgments (e.g., Durif et al., Citation2012; Sun et al., Citation2021). During the green purchasing process, how men and women cope with this uncertainty differs based on gender socialization, different value orientations, and social/biological roles (Saad and Gill, Citation2000; Zelezny et al., Citation2000; Essiz and Mandrik, Citation2022). Although men and women both may be inclined strongly toward green consumption or hold high levels of subjective knowledge, it is plausible to argue that their risk postures may be distinct from each other.

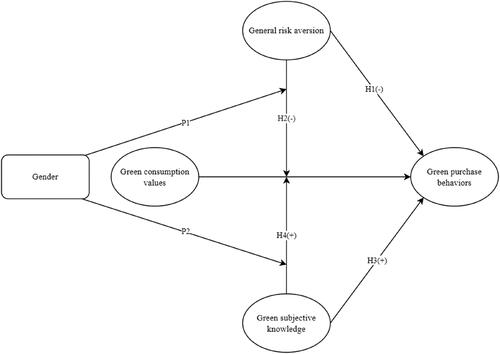

Based on the preceding review, we posit that men and women may naturally vary in terms of their general risk aversion and subjective knowledge, and this difference may in turn affect the green value-action translation process. However, based on the equivocal findings outlined above, we are unable to predict direction of influence. Nonetheless, acknowledging the general stereotype that green consumers from collectivistic countries like Turkey (from which our sample is drawn) tend to be females who are more competent (compared to males) while engaging in green behaviors (Bulut et al., Citation2017; Essiz and Mandrik, Citation2022), we expect women to hold higher levels of green values and behaviors compared to men and show greater value-action consistency. Although not stated as hypotheses, we include gender in our theoretical research model (see ) and make the following propositions:

P1. Gender conditionally interacts with general risk aversion on the relationship between green consumption values and green purchase behaviors.

P2. Gender conditionally interacts with green subjective knowledge on the relationship between green consumption values and green purchase behaviors.

Methodology

Consistent with previous studies on the theoretical notion of the green gap (Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Park and Lin, Citation2020; Chatterjee et al., Citation2021), we follow a deductive approach and choose a quantitative-based research methodology, involving a structured and self-administrated online survey. Data were collected using an online platform (Google Forms) given that the main survey was administrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it allowed us to reach distant respondents throughout the country. Besides, other rationales behind following an online survey method were threefold: (1) to concur with theoretical perspectives of rational economic paradigm, (2) to conserve resources and reduce the carbon footprint, and (3) to reduce nonresponse bias.

Research context

Early environmental behavior research largely focused on developed Western countries, yet research in developing countries like Turkey is still limited (e.g., Essiz and Mandrik, Citation2022). Realizing the heightened role of developing countries in decreasing global environmental degradation and recognizing the paucity of green gap research in Turkey, we decided to obtain quantitative data from the sampling frame of Turkish consumers. With an SDG Index Rank of 71 out of 163 countries, Turkey, the nineteenth largest developing economy in the world, has made significant progress in all three dimensions of sustainable development and is actively raising awareness of consumers and producers about sustainable consumption and production (i.e., SDG 12) through the national action plan and sectoral strategies (European Environment Agency, Citation2020). These reforms at institutional and sectoral levels point to room for improvement as well as the market potential for green products. Turkey, therefore, offers an interesting research context for quantifying the (in)consistency between consumer values and behaviors toward green products purchase.

Sampling strategy and participants

We recruited random Turkish nationals consisting of male and female consumers who accepted to participate in the study in exchange for the chance to win an Amazon eGift Card ($50) via lottery. Following the random sampling method, the survey was spread through social networks as well as among online college student and several consumer groups from different areas of the country to ensure a heterogenous sample, with reminder posts, sent each week to recruit new participants. The random sampling approach was deemed to be most appropriate for this study, as the use of purposive, convenience or any other non-probability sampling methods in green gap research is a methodological flaw from which many studies suffer. In nonrandom sampling methods, purposefully recruiting green consumers who are already manifesting the green gap or filtering subjects based on the degree of greenness, familiarity, and knowledge about green products potentially causes an overestimation of the value-action gap and creates measurement errors (for further discussion of this issue, see ElHaffar et al., Citation2020, p. 9). Given that one of our focal constructs is green subjective knowledge, recruiting consumers who are already familiar with the topic of green consumption via nonrandom sampling could have posed a serious threat to the study’s validity because of range restriction. To rule out this bias, ElHaffar et al. (Citation2020) suggest using random samples in green gap research. We thus used random sampling, which allowed inclusion of a range of green and non-green consumers and provided sufficient variability in our measures, enabling unbiased estimation of factors influencing the green gap.

Participants in our sample were constrained to be from age 18 to 55. This age group largely constitutes three generational cohort members, namely, Gen Z, Gen Y, and Gen X (Casalegno et al., Citation2022). These three cohorts were chosen because they hold lower levels of unneeded consumption behavior, as opposed to Baby Boomers in Turkey (Bulut et al., Citation2017). There are approximately 43 million people in Turkey in this age group (DataReportal, Citation2022). To represent this population, we estimated an ideal sample size of 271 participants through Qualtrics’s (Citation2020) assessment tool with a 5% margin of error. To account for probable cases of incomplete data, we recruited a sample of 350 participants. Then, a final number of 328 valid responses were obtained after excluding those who failed an attention check (see Appendix A) and/or provided incomplete answers. In addition, a power analysis using G-power 3.1 indicated that 328 participants were sufficient for this study to detect a medium effect size with 80% power at the a level of 0.05, as recommended for behavioral studies (Cohen, Citation1988). The key demographic characteristics of the sample is presented in . The sample heterogeneity bears similarities with other country-specific green gap research (e.g., Nguyen et al., Citation2019), representing characteristics of typical consumers in major urban areas of Turkey.

Table 2. Sample characteristics.

Measures and operationalization of variables

Multi-item scales operationalized in past research were used to measure the constructs of this study. First, the main dependent variable of this study is green purchase behaviors. To capture this construct, we adapted three items (original α = .93) from Taylor and Todd (Citation1995) and three items (original α = .77) from Lu et al. (Citation2015). Next, the green consumption values construct is the main explanatory variable. Six items from the “GREEN scale” of Haws et al. (Citation2014) (original α = .95) were taken to assess green values.

For the moderators in the study, we measured risk aversion by employing six items from the general risk aversion scale (original α = .72) of Mandrik and Bao (Citation2005). Compared to past risk aversion measures that either employ choice dilemmas or gambling preferences, the general risk aversion scale of Mandrik and Bao (Citation2005) is simpler and shorter because it is domain-agnostic, making it more applicable in a wide variety of contexts. Last of all, green subjective knowledge as the second moderator was measured by adapting four items (original α = .81) from Essiz and Mandrik (Citation2022), a shortened and modified version of the subjective knowledge measure of Flynn and Goldsmith (Citation1999) and three items (original α = .74) from Redman and Redman (Citation2014). We attempted to cover a broad array of abstract knowledge by including measurement items in relation to green consumption practices, green product quality, social and environmental justice, recycling, sustainable giving, and organic waste configuration. Detailed measurement items are presented in Appendix A.

Survey design

The main questionnaire was initially designed in English to maintain the originality and consistency of adapted measurement scales. To ensure the face validity of the measures, we then created the Turkish version of the questionnaire by following the parallel back-translation method. The survey instrument was translated and back-translated independently by two Turkish-English bilinguals, then the back-translated versions were compared. Any disputes were resolved through discussions among translators and principal investigators to maintain uniformity between the two language versions and to make sure the translated version would be correctly understood by the Turkish sample. To ensure that subjects understand and interpret the concept of green consumption in the same way, the concept definition was presented before presenting questions related to constructs of the study in line with early recommendations (Chatterjee et al., Citation2021). Overall, the survey instrument had four sections: participants indicated their level of agreement on 5-point Likert scales (1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”) to questions regarding green consumption values and purchase behaviors (part one), green subjective knowledge (part two), general risk aversion (part three), and finally they filled out related demographic information (part four) and were thanked for participation.

Pilot study

Before launching the main survey, we conducted an initial pilot study to evaluate the content validity of the measurement scales, a vital prerequisite for establishing construct validity (e.g., Rossiter, Citation2008). All measures used in the study were based on existing scales for general risk aversion, subjective knowledge, green values, and purchase behaviors, using all scales in their entirety. This enabled us to ensure content validity and to preserve the psychometric properties of the original scales. In line with sample size recommendations of Julious (Citation2005) for pilot testing, the survey was initially cross-judged in terms of wording, instrument length, and questionnaire format by two marketing faculty members in the field. Afterward, the questionnaire was administered to a voluntary response sample of twelve Turkish graduate students who were majoring in the field of sustainability at a large state university. They were invited to answer, review, and critique back-translated versions of the questionnaire. Finally, the questionnaire was slightly reworded and finalized to make all the questions clearer based on their feedback.

Social desirability bias

It is generally accepted that self-administered web-based questionnaires (as in this study) tend to be less vulnerable to social desirability bias than interviewer-administrated questionnaires, since they reduce the salience of social cues by isolating subjects to some degree (see Kreuter et al., Citation2008 for a discussion). However, considering that green consumption is an ethical matter, consumers may still tend to exaggerate their intentions to answer in a socially desirable way regardless of the surveying technique. We thus took several procedural steps during data collection to minimize this potential threat and enhance authenticity of responses.

Following recommendations of Kreuter et al. (Citation2008), participation in our study was completely voluntary; moreover, anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed with an informed consent form provided at the beginning of the questionnaire. Respondents were also assured that there were no right or wrong answers. Besides, dependent and explanatory variables of the study were introduced on different pages of the online survey, inhibiting participants from extrapolating cause-effect relationships among constructs. These procedures minimized the interviewer bias and made participants less likely to edit their responses to be more socially desirable.

Results

Validity

To test the validity of the measurement model, we initially performed an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) by following the principal components method and varimax rotation. Originally, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) scores ranged between 0.86 and 0.89 for all constructs, where the sampling adequacy was ensured by exceeding the minimum level of 0.60 (Cerny and Kaiser, Citation1977). On top of that, Bartlett’s test of sphericity for each construct was found to be significant (p < .00); thus, preliminary factor analysis conditions were satisfied. In the EFA, standardized items were loaded on four components and Eigen values exceeded one. All standardized factor loadings (see Appendix A) were found to be large enough (between 0.71 and 0.87, p < .001) and successfully explained the total variance of 0.81 in the measurement model, surpassing the cutoff limit of 0.60 recommended by Hair et al. (Citation2010).

After the measurement was shown to be valid for each construct, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to analyze the model fit. We treated every construct as a distinct measure in the CFA, where each observed variable was linked to its respective latent variable. Hence, we formed a single hypothetical measurement model. Overall fit indices of our model were noted as follows: GFI = 0.95, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.97, NFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.017, χ2/df = 2.91, p > .05. Results indicated a good fit between our data and measurement model (Hair et al., Citation2010). In general, this outcome along with initial EFA results provide statistical evidence for the content and construct validity, denoting that observed variables significantly explained the variance of their respective latent constructs.

As a rigorous measure of convergent validity, average variance extracted (AVE) scores were computed and surpassed the minimum limit of 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker, Citation1981). In parallel, we evaluated the discriminant validity of our constructs through Fornell-Larcker and HTMT criteria, per the suggestion of Awang (Citation2014). Based on the Fornell-Larcker approach, we discovered that the square root of the AVE of each construct was greater than the inter-constructed correlations (Fornell and Larcker, Citation1981). The HTMT ratios of all constructs (one-tailed test, p < .05) were also found to be lower than the conservative cutoff value of 0.85 (Henseler et al., Citation2015), demonstrating the data did not suffer from construct redundancy problems.

We finalized our validity assessment by using the single control question which rates the importance of sustainability for participants. We wanted to see if this measure positively correlated with green values and behaviors. Strong correlation sizes were observed (r = .432GCVs, p < .01; r = .396GPBs, p < .01), indicating that as participants hold higher GCVs and GPBs, they cared more about sustainability, as should be expected. To some degree, these positive relationships signal that participants provided meaningful answers to scale items related to green values and behaviors. Based on these findings, we conclude that the nomological network depicted by the model constructs is represented with adequate validity by our measures.

Reliability

To test the internal consistency of the four multi-item scales used in the study, we evaluated both composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha (see ). Both CR values and alpha coefficients exceeded the minimum limit of 0.70 (Nunnally, Citation1978), showing an adequate reliability. Taken together, provides a summary of validity and reliability results.

Table 3. Construct validity and reliability.

Nonresponse bias and common method variance

As data was gathered from participants in multiple waves, potential nonresponse bias was evaluated using Levene’s homogeneity of variance test, to understand if there is homoscedasticity across our sample group. For this cause, we classified 153 participants as “early respondents” who participated within four weeks, and 175 as “late respondents” who participated from four to eight weeks later. Levene’s test for all four constructs was found to be not significant (p > .05), signaling homogeneity of variance in measures. Moreover, checking the equality of means with a t-test showed no significant differences between those of early and late participants (Armstrong and Overton, Citation1977), indicating no threat of nonresponse bias.

We next accounted for common method variance (CMV) as it may lead to Type I and II measurement errors by inflating the relationship among constructs (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). We conducted Harman’s one-factor test (Harman, Citation1976) by running an EFA with unrotated principal components. All dependent and explanatory variables were combined into a single factor, where the single factor accounted only 30.05% of the total observed variance, posing no risk for CMV. We additionally employed a common latent factor analysis, where we ran a CFA with and without the presence of common latent factors. This allowed us to compare differences in standardized regression weights. The differences were small and did not exceed the cutoff limit of 0.20 recommended by Cohen (Citation1988). Finally, we conducted a full collinearity test based on variance inflation factors (VIFs), where VIF values fluctuated between 1.103 and 4.039, not exceeding the 5.0 threshold (Hair et al., Citation2010), providing statistical evidence for the absence of a common method bias.

Preliminary statistics

Before proceeding with hypothesis and proposition tests, we report basic descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations to provide initial insights into the structure of relationships among measurement constructs (see ). The data followed a normal distribution, and multicollinearity was not observed as the skewness and kurtosis values fall within the acceptable range of −2 and +2, respectively (George and Mallery, Citation2010). Expectedly, participants hold greater values toward green consumption (M = 3.36, SD = 1.06) and moderately lower purchase behaviors (M = 3.11, SD = 1.20), offering preliminary indication of the green value-action gap (t-value = 3.07, p < .01). Notably, there was a moderate negative relationship between general risk aversion and green consumption values (r = −.35, p < .001) and with purchase behaviors (r = −.31, p < .001), signaling potency for the direct negative affect and moderating role of general risk aversion. In addition, green subjective knowledge was positively associated with green consumption values (r = .33, p < .001) and purchase behaviors (r = .36, p < .001), giving us early confidence for the potential direct positive affect and moderating role of this construct. Finally, we found significant negative correlation between general risk aversion and green subjective knowledge constructs (r = −.32, p < .001), preliminary suggesting that participants with high green subjective knowledge may be more inclined to take risky decisions.

Table 4. Pearson correlations and descriptive statistics.

Hypotheses and propositions tests

The moderator variable decides under what conditions and for how long the explanatory variable affects the outcome variable (Baron and Kenny, Citation1986). To test direct and categorical moderating affects, Hayes’s (Citation2017) PROCESS V4.0 computational macro tool was utilized. The PROCESS tool uses a bias-corrected bootstrapping technique to generate confidence intervals (Preacher and Hayes, Citation2008), assisting us to address potential bias problems arising from asymmetric sampling distributions of indirect effects.

In testing our hypotheses and propositions, we employed Model 2 and Model 3 to capture two and three-way interaction effects separately (Hayes, Citation2017). For both models, we first averaged item scores of each factor to form the total variable factor, then we set five thousand bootstrap resamples to calculate 95% bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals of indirect effects. Hence, variables that constitute interaction products were standardized and mean-centered to avoid multicollinearity issues as well as to enhance interpretability of outcomes.

Testing hypotheses

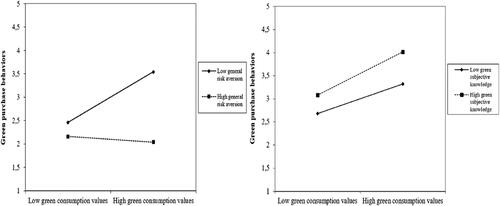

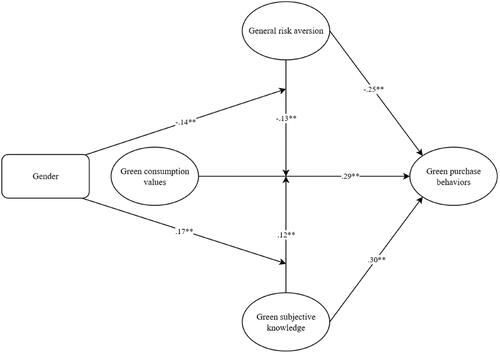

Hypotheses 1 and 3 focus on the direct influence of risk aversion and subjective knowledge on green purchase behaviors. Meanwhile, hypotheses 2 and 4 deal with moderating effects of these constructs. We tested these hypotheses through Model 2, where we choose risk aversion and subjective knowledge as multiple moderators and green consumption values as the explanatory variable to predict the outcome variable of green purchase behaviors. The overall regression model was significant (F (3, 384) = 183.7, p < .01) with R2 = .69. Multicollinearity did not pose an issue in the model, as collinearity tolerances were greater than .80 and VIFs ranged between 1.03 and 1.28, within acceptable thresholds (Hair et al., Citation2010). The direct relationship among dual moderators and green purchase behaviors were significant (GRA→GPBs = β = −.25, t-value = −4.52, p < .01, ΔR2 = .14, 95% CI = [−.34, −.15]; GSK→GPBs = β = .30, t-value = 4.02, p < .01, ΔR2 = .16, 95% CI = [.15, .45]) after controlling for background differences. Within the limits of confidence intervals (95%), two-way interaction effects of risk aversion (β = −.13, t-value = −3.15, p < .01, ΔR2 = .11, 95% CI = [−.16, −.09]) and subjective knowledge (β = .12, t-value = 3.24, p < .01, ΔR2 = .13, 95% CI = [.10, .13]) were significant on the relationship between green consumption values and purchase behaviors by accounting substantial change in the predictive power of the whole regression model. Detailed results are presented in .

Table 5. Direct and moderating effects of general risk aversion and green subjective knowledge.

Next, we show conditional interaction effects in . It appears that the relationship between green values and purchase behaviors is significant and more positive when risk aversion is low (β = .26, SE = .04, p < .01) and subjective knowledge is high (β = .29, SE = .03, p < .01). This suggests that consumers who are more risk-tolerant or the ones who hold superior green subjective knowledge translated their green values into actual purchase actions more swiftly than their high risk-averse and low-knowledge counterparts. Taken together, all four hypotheses are supported. Finally, the significant three-way interaction effect (β = −.14, t-value = −2.06, p < .05, ΔR2 = .09, 95% CI = [−.21, −.06]) among green values, risk aversion, and subjective knowledge offered a potential reason for the preceding result: as participants hold greater subjective knowledge, they are more willing to take risks, and in turn, are more willing to translate their values into actions.

Testing propositions

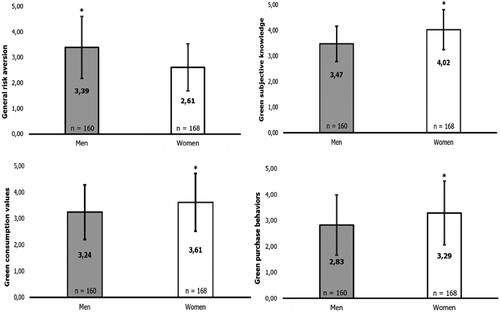

Propositions 1 and 2 relate to the categorical moderation effect of the gender. Primarily, we found differences between means of women and men in terms of their risk aversion (Mwomen = 2.61, SD = 0.92 vs. Mmen = 3.39, SD = 1.21, t-value = −6.59, p < .01), subjective knowledge (Mwomen = 4.02, SD = 0.78 vs. Mmen = 3.47, SD = 0.69, t-value = 6.75, p < .01), green values (Mwomen = 3.61, SD = 1.10 vs. Mmen = 3.24, SD = 1.03, t-value = 3.14, p < .01), and purchase behaviors (Mwomen = 3.29, SD = 1.23 vs. Mmen = 2.83, SD = 1.16, t-value = 3.48, p < .01) (see ). A greater value-action inconsistency was noted among men (t-value = 3.33, p < .01) as opposed to women (t-value = 2.51, p < .01), providing motivation to explore further potential conditional interaction effects of gender.

Figure 3. Gender differences on main constructs (±Error bars represent standard deviations, *p < .01).

Two multiple regressions were performed to test our propositions via Model 3. In the first model, we selected green values as the explanatory variable, green purchase behaviors as the dependent variable, risk aversion as the continuous moderator, and gender as the categorical moderator to account for three-way interaction terms. In the second model, subjective knowledge was the continuous moderator and other variables remained the same. Three-way interaction terms (green values × risk aversion × gender) (β = −.14, t-value = −4.12, p < .01, ΔR2 = 0.06, 95% CI = [−.11, −.26]) and (green values × subjective knowledge × gender) (β = .17, t-value = 4.93, p < .01, ΔR2 = 0.08, 95% CI = [.12, .25]) were significant in predicting green purchase behaviors. Therefore, gender significantly interacts with our dual moderators and both propositions are supported.

As a further line of investigation, we revealed that this moderated moderation effect was only significant for women (p < .01), not for men (p = .19). Specifically, three-way interaction effects were significant when the risk aversion of women is low (β = −.17, SE = .02, p < .01) and subjective knowledge is high (β = .19, SE = .01, p < .01), indicating more favorable green value-action translation for women with such traits. Finally, our analysis revealed that the low-risk-averse women group were likewise more likely to turn their green values into purchase behaviors, compared to low risk-averse men group (t-value = 7.15, p < .01). Expectedly, gender differences between subjective knowledge of participants were similarly observable, where high knowledgeable women were more likely to translate their green values into action, as opposed to high knowledgeable men (t-value = 5.84, p < .01). Meanwhile, green values still predicted purchase behaviors after accounting for the role of gender (β = .29, p < .01) and interaction effects of focal moderators remained significant. Overall, depicts a summary of this study’s main results.

Discussion of the results

Our results were robust and comported with those of other country-specific green gap research (Chaihanchanchai and Anantachart, Citation2022; Casais and Faria, Citation2022; Nguyen et al., Citation2019) by originally showing the existence of the recurring value-action gap among Turkish consumers. Similar to past green gap research in developing economies (e.g., Nguyen et al., Citation2019), it appears that the current sample likewise is not fully ready to prioritize green consumption, perhaps being constrained by other priorities (e.g., certainty, comfort, convenience) in life, even if their impulse to go green appears to be strong.

For the most part, past research does not address the roles of psychographic factors in understanding the green value-action relationship. In turn, the current study provides a new explanation to the green gap with dual moderating effect. Specifically, under higher degrees of risk aversion, we noted a larger gap among consumers; yet it was smaller for lower levels of the risk moderator, designating that consumers are more willing to convert their green values into action when they are more risk-tolerant. This outcome is reasonable given that consumers’ risk perception may vary based on different external contexts, situations, or pressures that may result from economic and societal changes, such as environmental degradation (Durif et al., Citation2012). This result is also in line with the latest research that shows a negative association between risk perception and willingness to engage in green behaviors (Saari et al., Citation2021). One sensible intuition behind this finding is that consumers may perceive higher financial, functional, or psychological risks while purchasing green products compared to conventional offerings, hence creating a dilemma or tradeoff of greater cognitive effort on information processing (e.g., Gürhan-Canli and Batra, Citation2004). Another reasonable explanation is that consumers may choose to behave egoistically by prioritizing their own psychological and physical needs over altruistic values and behaviors when they hold higher risk perceptions (Sun et al., Citation2021).

Next, we observed that subjective knowledge was successful in predicting green purchase behaviors in which consumers with higher degrees of subjective knowledge showed more consistency (i.e., a smaller green gap). This finding comports with the contention that cultivating environmental knowledge and awareness are effective means of promoting positive green behaviors (Meyer, Citation2015), as consumers with higher environmental knowledge can be more receptive to green products and show higher involvement levels, thus be more willing to engage in corresponding actions (Vermeir and Verbeke, Citation2006). This result is also in line with Gleim and Lawson (Citation2014) who argued that lack of environmental consciousness and social awareness toward green consumption may widen the gap between values and actions. Further, in our research model, the dual moderators significantly interacted with each other to predict purchase behaviors. This is reasonable, since knowledge has been conceptualized as one factor influencing risk perception, such that consumers behave and take risks based on their knowledge (Saari et al., Citation2021). It appears that subjective knowledge is an important precondition for risk assessment and green consumption. This is sensible in this esoteric consumption domain because if individuals do not hold sufficient knowledge, they may not appropriately judge risks toward green products.

Admittedly, gender was relatively underexplored in the context of the green gap and the generally inconsistent findings made it difficult to formulate any propositions for this variable. To mitigate this gap, this study adds to the scant green research on gender differences by demonstrating the categorical moderating role of gender on the green gap, helping to resolve conflicting theoretical findings. Our data reveal that men and women hold different degrees of risk aversion and subjective knowledge, as well as green values and behaviors. In particular, females seem to be more ready to bridge the green gap by showing less inconsistency between their values and behaviors. This could arise because females in our sample held a greater degree of subjective knowledge and, in turn, were more willing to afford risks compared to males. It is also conceivable that women in our sample might have paid more attention to environmental problems and hold higher prosocial status perceptions due to their knowledge level, in turn more readily translating their values to behaviors. Based on the evolutionary perspective of consumption, this finding supports the view of Brough et al. (Citation2016), in which the prevalent association between femininity and green behavior may be attributed to a gender-based inside-outside division of household responsibilities in relation to green consumption practices wherein females usually perform more active roles (see also Grønhøj and Ölander, Citation2007).

Contributions of the study

Theoretical contributions

Compared to most studies that used TPB to quantify the green gap (e.g., Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Park and Lin, Citation2020; Chaihanchanchai and Anantachart, Citation2022), we adopted a different socio-psychological lens – the value basis theory (Stern and Dietz, Citation1994). Like TPB, this multidimensional theory is a useful rational economic paradigm, yet explains the direct influence of personal and consumption values on the behaviors of consumers in an environmentalist context, making it an appropriate framework to shed light on the value-action discrepancy (Stern and Dietz, Citation1994).

A fundamental notion of Stern and Dietz’s (Citation1994) theoretical formulation is that relationships between green values and behaviors should flow in a causal chain in which consumers seek to maximize their utility through their consumption choices. From this perspective, some past research considered values as closely related, if not wholly coterminous with behaviors (see Liu et al., Citation2017 for a discussion). However, this perspective neglects the gravity of the value-action inconsistency, and it may inhibit researchers from investigating moderator variables which influence the translation of values into behaviors. Although the assumption of a direct link between values and behaviors may hold true in some consumption domains, the fact that values often do not translate to behavior in the green consumption domain should be attributed to the effect of moderators (Peattie, Citation2010; Nguyen et al., Citation2019). However, the value-basis paradigm of Stern and Dietz (Citation1994) does not explicitly account for moderation by various psychographic traits in the value-action transformation process due to its hierarchical flow.

Against this backdrop, we offer several contributions to theory. First, we corroborate the value-basis paradigm by empirically reconfirming the determinant role of values in explaining behaviors within the new setting of a developing country (Turkey), while at the same time, demonstrating that there remains a gap between values and behaviors, at least in the domain of green consumption. Second, building on its basic proposition that green values are believed to be directed by internal factors of consumers while explaining purchase behaviors (Stern and Dietz, Citation1994), we offer a novel theoretical addition by integrating this theory with two new dual moderators: (1) general risk aversion and (2) subjective knowledge, combined with a categorical boundary condition: gender differences in green value structures of men and women. These conceptual additions extend results of earlier studies (e.g., Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Park and Lin, Citation2020; Chaihanchanchai and Anantachart, Citation2022) and help increase our understanding of the green gap. We believe that our extended theoretical model could be adopted in various green domains where the value-action gap is salient, such as sustainable luxury, consumer ethics, energy use, and technological adoption (e.g., Park and Lin, Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2021).

Besides contributing to theory development, this study makes several methodological contributions. First, this research employed the general risk aversion measure (as opposed to domain-specific measures of risk aversion) and provided an initial demonstration of its utility in green consumer behavior research. Next, compared to existing domain-specific green gap research (e.g., Bodur et al., Citation2015; Davari and Strutton, Citation2014; Tung et al., Citation2012), the measurement scales utilized here covered a broader range of green values and behaviors while still effectively capturing the existence of the green gap.

Managerial implications

Promoting sustainability is a priority for many businesses and a struggle for them as they seek to differentiate their green offerings from standard ones. The green value-action gap therefore merits closer attention from them, as it is an important marketplace paradox and a daunting real-world challenge whilst implementing green marketing strategies (Park and Lin, Citation2020). Consumers who are averse to risk or who possess low green consumption knowledge may find it more difficult to purchase green products, even while they are generally sustainability oriented, as in this sample. Our findings support that the attitude-behavior gap can be reduced by incorporating concepts of general risk aversion and green knowledge while communicating environmentally friendly marketing messages. Managers can use this information to help segment the green consumer market, along with other segmentation variables, and seek ways of reducing risk perception, and capitalizing on green consumption knowledge to trigger purchases. Intriguingly, our results suggest that females feel more competent and less risk-averse compared to males in green purchasing. Building on this outcome, marketers of green products may particularly consider implementing an influencer or pull-marketing approach via females, in turn, guide males within the family or romantic relationships. Of course, marketers of green products must find ways to reduce perceptions of risks associated with product performance, quality, and value. To that end, our findings recommend that males may require different green communication strategies and even higher risk reduction efforts; hence, while marketing green products, retailers may consider introducing special offers (e.g., free trials, discounts, money-back guarantees) aimed toward men.

Realizing the current prominence of social media marketing strategies, marketers may use social media to disseminate promotional messages encouraging green consumption and risk-taking behavior or follow the buzz and conversational marketing strategies (e.g., storytelling activities, creating support systems via chatbots) to regularly advise consumers on their green product offerings and establish brand trust with the aim of counterbalancing the adverse effect of high perceived risk. During these times, green retailers may also engage in co-branding and umbrella branding activities with other well-known brands to mitigate risk perception toward their offerings, as consumers hold more positive behaviors toward co-branded products when it comes to green consumption (Heinl et al., Citation2021). To bridge the attitude-behavior gap efficiently, green products should be ultimately promoted and positioned as a utility-maximizing opportunity instead of solely positioning them as a pro-social solution; that is, green products must be perceived as personally beneficial. This may facilitate a favorable shift toward green purchasing by urging consumers to afford more risks when it comes to green consumption.

Besides emphasizing the sustainability impacts of green products by including detailed information about such things as environmental safety, labor practices, production process, and transparency in marketing communications, our findings also suggest the importance for public policy guidelines of educating consumers about green consumption practices in general. Hence, practitioners may accentuate the role of green knowledge and highlight the severity of global and local ecological risks during the preparation of environmental campaigns and education materials. A highly knowledgeable green consumer seems to be a highly reachable one.

Limitations and recommendations for future caveats

As in all empirical research, our study suffers from limitations, some of which may provide a baseline for future investigations. First, our research relies on a self-report survey that asks about behaviors, but we did not observe them through time. As self-reported green values and behaviors may be overstated (see Peattie, Citation2010, p. 214 for the discussion), potential measurement errors and psychological biases seem inevitable. To counter this effect, future research may use behavioroid measures or examine actual behaviors on specific green products. Future research may employ methodological triangulations and experimental approaches with stimuli that differ in regard to their sustainability and value characteristics, in order to better approximate the green gap and examine how it is affected by risk aversion, green knowledge, and gender. For instance, experiments that use priming methodology can be viable methods to gather behavioral data. Given the rarity of priming research in the green consumption realm, it would be appealing to prime personal values, brand characteristics, advertising appeals, and different social goals to trace the effects of priming on the value-action relationship (e.g., Amatulli et al., Citation2019).

As risk perceptions also may vary depending on product categories (e.g., convenience, specialty, unsought, and durable goods), the value-action gap will be contingent on such product types (Park and Lin, Citation2020; Schäufele and Janssen, Citation2021) and should be conceptualized separately. Future work can examine risk traits of consumers and specific facets of perceived risk (e.g., psychological, social, performance, financial) which are related to green consumption activities, and each may have different implications for green consumption. While predicting green behaviors, future efforts may also keep an eye on different types of values rather than only focusing on environmental values as this may provide more intuitions into the gap. Ultimately, future efforts should incorporate moderating effects of other psychographic traits such as loss aversion, green trust, and greenwashing perception (Li et al., Citation2021), situational and contextual affordances (Nguyen et al., Citation2019), social factors (Essiz and Mandrik, Citation2022), and dimensions that are listed under Peattie’s (Citation2010) conceptualizations (e.g., product/consumer confidence and willingness to compromise) to better profile the green gap.

Another limitation is that our dataset is a cross-sectional one among Turkish consumers; hence, we do not neglect the possibility that our predictor relationships may differ based on the structure of another green product market and level of market saturation. To some degree, this limits the generalizability of our findings. Among our measured constructs, cross-sectional age differences could not be reliably observed, attributing to the asymmetric distribution of the relatively small sample size. With a longitudinal approach and a wider distribution of values in the empirical data, future work may examine specific age groups, dyad partners (e.g., Senyuz and Hasford, Citation2022), the role of culture, and other demographics (e.g., social class) in their effect on value-action translation. We also recognize that our focal constructs may vary with income (Saari et al., Citation2021) and education levels (Sun et al., Citation2019). As we did not include them for examination here due to limited variation in the data, income and education should be examined as categorical factors in future research.

Conclusion

By quantifying the existence of the green gap in a developing country (Turkey), this empirical study seeks to illuminate the green consumption process and urges accountable stakeholders to capitalize on general concepts of risk aversion, subjective knowledge, and gender differences in the process of understanding and strengthening the green value-action relationship. By initiating this line of inquiry, our study is the first to distinguish and test these individual difference variables which moderate the relationship from green values to action, identifying dual psychographic and single categorical boundary conditions that impact the green gap. At the macro-level outlook, the attitude-behavior gap is evolving every day, owing to continual changes in the lifestyles of consumers that are brought by modernization and the advent of technology. Therefore, this research domain demands further academic and practical attention, in particular from high-impact and developing regions, in order to mitigate unsustainable consumer behaviors, with the goal of safeguarding global sustainable development goals.

Ethical statement

In this study, all procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or with comparable ethical standards. Informed consent form was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgments

The open-access funding enabled by CEU Library. We are grateful to associate/production editors and anonymous reviewers for their inputs.

Data availability statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Abrar, M., Sibtain, M. M., & Shabbir, R. (2021). Understanding purchase intention towards eco-friendly clothing for generation Y & Z. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1997247. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1997247

- Aertsens, J., Mondelaers, K., Verbeke, W., Buysse, J., & Van Huylenbroeck, G. (2011). The influence of subjective and objective knowledge on attitude, motivations and consumption of organic food. British Food Journal, 113(11), 1353–1378. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701111179988

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Amatulli, C., De Angelis, M., Peluso, A. M., Soscia, I., & Guido, G. (2019). The effect of negative message framing on green consumption: An investigation of the role of shame. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(4), 1111–1132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3644-x

- Aren, S., & Hamamci, H. N. (2020). Relationship between risk aversion, risky investment intention, investment choices: Impact of personality traits and emotion. Kybernetes, 49(11), 2651–2682. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-07-2019-0455

- Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377701400320

- Awang, Z. (2014). A handbook on SEM for academicians and practitioners: The step-by-step practical guides for the beginners. Bandar Baru Bangi, MPWS Rich Resources, 10(3), 32–45.

- Bailey, A. A., Mishra, A. S., & Tiamiyu, M. F. (2018). Application of GREEN scale to understanding US consumer response to green marketing communications. Psychology & Marketing, 35(11), 863–875. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21140

- Bao, Y., Zhou, K. Z., & Su, C. (2003). Face consciousness and risk aversion: Do they affect consumer decision‐making? Psychology and Marketing, 20(8), 733–755. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10094

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Bauer, R. A. (1960). Consumer behavior as risk taking. In Proceedings of the 43rd National Conference of the American Marketing Assocation, June 15, 16, 17, Chicago, IL, 1960. American Marketing Association.

- Berki-Kiss, D., & Menrad, K. (2022). Ethical consumption: Influencing factors of consumer’s intention to purchase Fairtrade roses. Cleaner and Circular Bioeconomy, 2, 100008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcb.2022.100008

- Bodur, H. O., Duval, K. M., & Grohmann, B. (2015). Will you purchase environmentally friendly products? Using prediction requests to increase choice of sustainable products. Journal of Business Ethics, 129(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2143-6

- Brough, A. R., Wilkie, J. E., Ma, J., Isaac, M. S., & Gal, D. (2016). Is eco-friendly unmanly? The green-feminine stereotype and its effect on sustainable consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(4), 567–582. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw044

- Bulut, Z. A., Kökalan Çımrin, F., & Doğan, O. (2017). Gender, generation and sustainable consumption: Exploring the behaviour of consumers from Izmir, Turkey. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 41(6), 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12371

- Casais, B., & Faria, J. (2022). The intention-behavior gap in ethical consumption: Mediators, moderators and consumer profiles based on ethical priorities. Journal of Macromarketing, 42(1), 100–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/02761467211054836

- Casalegno, C., Candelo, E., & Santoro, G. (2022). Exploring the antecedents of green and sustainable purchase behaviour: A comparison among different generations. Psychology & Marketing, 39(5), 1007–1021. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21637

- Cerny, B. A., & Kaiser, H. F. (1977). A study of a measure of sampling adequacy for factor-analytic correlation matrices. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 12(1), 43–47. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr1201_3

- Chaihanchanchai, P., & Anantachart, S. (2022). Encouraging green product purchase: Green value and environmental knowledge as moderators of attitude and behavior relationship. Business Strategy and the Environment, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3130